I first met Stephen T. Vessels in a tiny French café in Southern California. He was enjoying a quiet Sunday brunch and I rudely interrupted him. The rest, as they say, is history.

Stephen’s first published novel, The Door of Tireless Pursuit, will be released next month through ShadowSpinners Press, one of a series of books by multiple authors that share the theme, Labyrinth of Souls. I recently had the great joy and privilege of sitting down with this gifted author, artist, and true renaissance man, to discuss his new books, his ballpoint pen drawings, and a few other musings I thought you might enjoy.

—

CM: This has been an eventful fifteen months for you, Stephen. You released your first story collection, The Mountain & The Vortex and Other Tales, through Muse Harbor Publishing, both in trade paper and hardback editions; your ballpoint pen drawings were exhibited in a solo exhibition at the Andre Zarre Gallery in Chelsea (NYC); you’ve been on panels at ThrillerFest and the World Fantasy Convention, and attended two World Science Fiction Conventions, in Kansas City and Helsinki, Finland. Your first published novel, The Door of Tireless Pursuit, will be released next month by ShadowSpinners Press. You’ve become communications director for the Classical Music website, Masterpiece Finder, as well as researcher and contributor, and somehow managed to fit in being an editor for my coloring book journal series. What’s your secret?

SV: No secret, just work. And getting a little better at functioning as a professional. The foundation of everything for me is the writing. If that isn’t happening nothing else works. It’s taken me awhile to figure out how I work. A really long while, because I’m stubborn. I’ve long been an advocate of writing every day. In spite of that I’ve been frustrated with my output for many years. The reason, now, is so obvious it’s embarrassing. I was giving too much time to revising in a way that was counter-productive. Other writers tried to tell me but I had to figure it out for myself. I’d write a chapter, revise, revise, revise; write another one, revise, revise, go back to the beginning, revise some more, inching my way forward like that. It’s a testament to my persistence that I ever finished anything doing that. I’ll never work that way again. But for me it isn’t just about writing in complete drafts; I need to produce new work every day. I snuck up on that understanding by drawing every day. Some people say stick to one medium. That doesn’t work for me. My writing supports my art and vice versa. Sort of – it’s more complicated than that. The other part is putting legs on the work, which is mostly about being willing to withstand however many no’s it takes to get a yes.

In the latter regard, working with you has been especially helpful. You’ve been a great champion of both my writing and my art, and understand better than I ever have, or likely ever will, how to promote work and get it out there without compromising integrity. I love working with you on your coloring book journals. That is a brilliant, brilliant project. It’s given me an opportunity to apply my skills in a way that directly benefits others, which has been a great gift.

CM: Who developed first, Stephen the writer or Stephen the artist? How did each of these passions first take hold in your heart?

SV: Well, I think I inherited both interests from my father. He was a bit of a frustrated writer. But he was never someone who viewed writing as a career. He lived through the Great Depression and World War II, and it made him very pragmatic. It’s ironic but understandable that he tried to dissuade me from going into this field. It was always very important to him to have a lot of books around, though. He was an avid reader and a prolific letter writer. My mother kept all the letters he sent to her while he was in Europe during the war, and it’s hundreds. I’ve got letters he wrote me that go on for twenty or thirty pages, handwritten on those yellow legal pads. He had a great love of literature, as well as art and music. I still have the copy of Treasure Island he gave me when I was a kid. He could recite long poems from memory: The Ballad of East and West and Gunga Din, by Kipling, and The Ballad of Sam Magee, by Robert Service, Kubla Khan, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. His favorite poem was Abu Ben Adhem, by Leigh Hunt.

The writing came first, for me. That was influenced also by film. I read Dracula and Frankenstein before I was ten, I think, as well as all the stories and poems of Edgar Allen Poe, and I loved the films of Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff, Peter Lorie, Vincent Price, Claude Rains, all those guys. I knew I wanted to write Science Fiction when I was very young. I read all the pulps – Analog, Galaxy, If, Fantasy and Science Fiction. The comics, too. Tales from the Crypt and Creepy. My brother and I were both very deep into SF and horror – that was a real bond between us. But I loved all literature; I’ve never been a respecter of categories. The first quote-unquote adult novel I read was Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott. I loved that book. Just fell into it. I read all the time. My parents took us on long road trips, usually traveling back and forth between Denver, where we lived, and south Texas, where my grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins mostly lived. My mother got on me a lot to stop reading and look at the scenery, told me I’d make myself carsick. I’d glance out the window and go back to my book, and I never got carsick. I loved books, pure and simple – having them, holding them, reading them, lining them up on the shelves. I started collecting books before I was ten, too. Joined the Science Fiction Book Club.

The art bug came from my dad, too. He was big on going to museums, and became a serious art collector. He would only collect from living artists whom he had met. He took me and my siblings to galleries with him, in Santa Fe and Taos and Mexico City. He took us all to Washington D.C. one year and we pretty much lived in the museums on the Mall for several days. Those are some of my fondest memories of my father. Those and going to concerts with him. He loved classical music and jazz.

CM: I read that you wrote your first story at the age of six. What was it about? What did 6-year-old Stephen believe about the world? How does that compare to what you believe about the world today?

SV: The first story I remember writing had borrowed characters. I think it had Dracula or Frankenstein duking it out with the Creature from the Black Lagoon, chasing each other around in a cave somewhere. Sort of like rudimentary fan fiction. There was another one, which I titled grandiosely, That Which Consumes, that was inspired by Ib Melchior’s movie, Journey to the Seventh Planet. I was six or seven when that movie came out. Some of that imagery filtered into my novella, The Mountain & The Vortex – I realized it after I’d written it. A creature like a gob of flesh with one big eye became a mountain with one big eye. So, you know, it’s all still in there. I don’t think those sorts of childhood influences go away.

I always had a taste for the unknown – the texture of the unknown. I’ve never liked the idea of a fixed reality. That was true then and it’s true now. I was more comfortable with conventional notions of good and evil, when I was a kid. Now I’m more sensitive to circumstances. Although, I’m not sure how true that really is. It never sat right with me, the way the Frankenstein monster died, with the villagers howling while he burned. James Whale got that right. It’s such a powerful scene. A burning windmill – it echoes Cervantes and Greek mythology. The real monster was the mob.

I was a very romantic-minded kid, and I’m still a romantic-minded adult. I was hopeful then and I’m hopeful now. I think there’s more sadness in me, now. But there was sadness in me when I was young, too. I think kids carry around more sadness than adults recognize, a lot of times. I see people more clearly, now – see myself more clearly. That’s life experience. The seeds of who I am were there early on.

CM: Over the course of your life, who and what have been some of your inspirations and influences?

SV: The biggest influence, again, was probably my father. Taking me to concerts, galleries and museums and feeding me books. My mother was a homemaker in the grand tradition – House Beautiful. She believed in living a gracious life with style. From her I got a sense of refinement. Probably my stubbornness, too. They were a formidable couple.

I’ve lived a life steeped in the arts, so specific influences are hard. Impossible, really. I have no idea how many books I’ve read, works of art I’ve seen, films I’ve watched, pieces of music I’ve listened to. I have a boundless appetite for story, image and sound.

Writers that come readily to mind: Dickens, Hemingway, George Elliot, Shakespeare, Asimov, Hermann Hesse, Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, H.P. Lovecraft, Samuel R. Delany, Louisa May Alcott, Ursula K. LeGuin. There are so many: Robert Silverberg, Roger Zelazny, Kate Chopin, J. D. Salinger, Virginia Woolf, John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Thomas Hardy, Eugene O’Neil, Samuel Beckett, Jorge Luis Borges, e.e. cummings, Allen Ginsberg, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle. Scratching the surface. When I was a kid I memorized Cyrano de Bergerac’s monologue about his nose. I read The Hobbit by flashlight under the sheets. Multiple times. I’m influenced to some extent by everything I read. Among contemporary writers Monte Schulz looms large, someone I’m proud to call a friend. His novel Crossing Eden is a masterpiece. He’s also been one of my greatest teachers. I’ve been privileged to study with Robert Olen Butler and Jane Smiley, and they’ve both left their marks on my process – brilliant, brilliant people. My mentors John R. Reed and Elizabeth Engstrom have had huge influences on me. I’ve never had a teacher I respect more than John. Sid Stebel and Karen Ford, as well. All the writers in the writing groups I belong to.

A lit professor I had in Colorado, Bruce Kawin, got me to read Ulysses, for which I will be forever grateful. I took Film Studies with him, too. He introduced me to Ingmar Bergman, Luis Bunuel, Federico Fellini, Akira Kurosawa and many others. We shared a passion for Hitchcock.

Art, for me, started with Van Gogh. And then just went everywhere. All the impressionists, especially Monet. Kandinsky, Rothko, Degas, John Singer Sergeant. It’s endless. Harry Reese, who taught me Book Arts at UCSB, has had a great influence on me as well – he and his wife Sandra. It was a great pleasure to get to apply some of what I learned from them, collaborating with the publishers in the design of The Mountain & The Vortex.

Music, too. Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Strauss, everything from Copland to Elliott Carter to Miles Davis. I’m so grateful to my parents for all the concerts they took me and my siblings to when we were kids. I love rock, too, and a broad spectrum of contemporary music. I’m a compulsive audiophile; at one time I had over six thousand CDs. Right now I’m immersed in discovering the works of hundreds of lesser known classical composers. There are massive archives on the internet.

CM: You seem to enjoy exploring darker subjects. Does your writing ever frighten you? What about your art?

SV: My stories don’t scare me. (My nightmares don’t either; I enjoy them.) I do sometimes find myself writing things that make me uncomfortable. I think that comes with delving into the imagination. I love creating a sense of the unknown. I love it because it expands the scope of life with mystery. There’s a scene in the last episode of True Detective, when Matthew McConaughey reaches the heart of the psychopath’s lair and has a vision of a cosmic vortex – that’s the business.

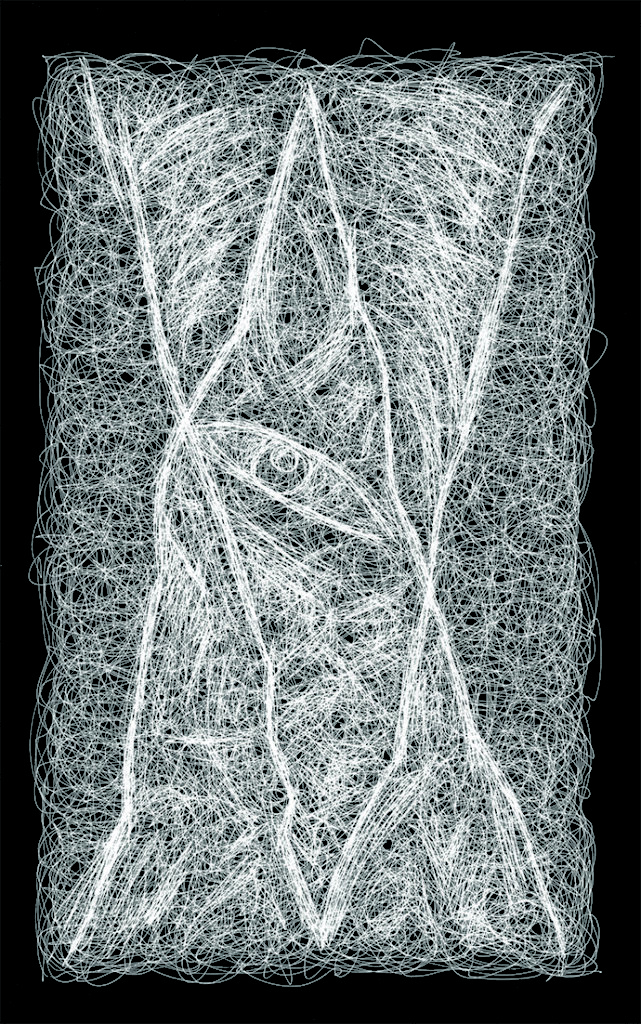

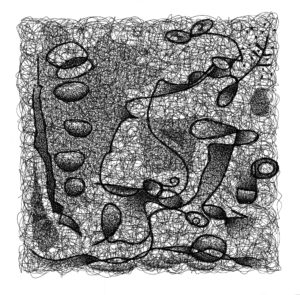

With art I’m preoccupied with fields, creating the sense of a penetrable barrier through which unknown things might emerge, or a visual field that invites projection. But I also like representation, particularly when it evokes a sense of duende. That’s not something I can explain. Garcia Lorca gave a lecture: Theory and Play of the Duende. You can find the English transcription online.

CM: What knots are you most interested in untangling with your work?

SV: For me, fiction is the conscience of belief. I’ve never been satisfied with the characterizations of reality presented by either science or religion. I don’t know if it’s exactly untangling anything, but both writing and art for me are undertakings of discovery. I’m more interested in finding out what I intend than knowing in advance.

CM: I know you are very active in the Santa Barbara Writers Conference. How important would you say it is to connect with other writers? How have those connections helped you to change and grow?

SV: Both writing and drawing are very solitary endeavors. One of the biggest mistakes I made was squirreling myself away with my work for years on end, without connecting with other writers. The Santa Barbara Writers Conference has been very important to me. I’ve made many close friends there. I live alone. It’s very easy for me to get enmired in my own swamp. I know a lot of other writers in similar circumstances. It’s incredibly supportive to spend time in the company of large groups of writers. We’re the only ones who know how hard it is to do what we do. Anyone who hasn’t tried it doesn’t know. The demands it makes on your faculties can overload your brain. That’s leaving out the impediments to getting published, and periodically marking time in front of the mirror wondering if you’re one of God’s mistakes. I love the community of writers. The vast majority of writers I’ve met are kind-hearted and generous. It’s also been extremely valuable to me to attend genre-related conventions, to be among people writing the kinds of stories I like to write. ThrillerFest in particular has been a boon to me. Conferences and conventions recharge my batteries. I come away motivated to keep at it. If I’d never gone to the Santa Barbara Writers Conference I think there’s a good chance I’d still be unpublished.

CM: You are also very active on Facebook and have cultivated a warm and genuine community online. How has it been, to observe and participate in that development, meeting new people and sharing your interests with friends and fans of your work?

SV: I got into social media kicking and screaming. I really looked down on it. Having been on Facebook for several years, now, I have to say I was wrong. Nothing beats meeting people in person, but Facebook is a great vehicle for connecting, especially if you live alone. I’ve stayed in touch with people I’ve met in my travels far better than I ever would have without it. I’ve also re-connected with old friends I hadn’t spoken to in decades. The most valuable thing for me has been the camaraderie and goodwill, and so that’s what I try to give back.

And I love sharing my work on there. I don’t really think of it as promotion. More just interaction. It’s so ephemeral, the way things slide down the chain so quickly. I’m not sure how well it really works as a promotional vehicle. Some, I’m sure. For me, though, it’s more about mutual support. I post a photo of a drawing and eighty or a hundred people like it and comment on it – that’s supportive. Two hundred plus birthday greetings is supportive. I finish a book or a story, stick my hand up and here comes everybody. Supportive. It’s wonderful.

It’s also fascinating. It’s a new form of communication that’s evolving as we watch. People posting all kinds of stuff – I learn things on there all the time. I ignore the contentious stuff, stick with the grand exchange.

I had an experience on Facebook that never would have happened without it. This is something that would have been utterly impossible fifteen or twenty years ago. There’s a huge database of obscure Classical music on YouTube. One evening I was listening to a piano sonata by Leo Ornstein, an American composer and pianist I’d just discovered. Lovely, lovely piece of music. I noticed that the recording had been made the previous year. So – now, mind you, I’m still listening to the piece for the first time – I Google the pianist, Arsentiy Kharitonov, and find out he’s teaching music theory in Houston. On a whim I look for him on Facebook, find him and send him a “friend” request. He accepts and I send him a message that I’m listening to his recording of Ornstein’s Sonata. He responds, and while I’m still listening to the piece for the first time, I’m engaged in an exchange about it with the man who performed it. That event has developed into both a friendship and a working relationship. Just incredible.

CM: What is a barcode poem? How did you come up with the idea? Do you have an example of a poem you’d like to share?

SV: About thirty years ago I invented a poetic form that utilizes barcodes to set syllabic line lengths and stanza breaks. It arose out of a long desire to have my own invented form, or “nonce form” in lofty parlance. An example of a nonce form poet is Maryanne Moore. The way she worked, she would compose a stanza of free verse, and then make the meter and syllabic line lengths of every subsequent verse agree with the first. I played around with a lot of things like that over the years, to no result I found satisfying. Everything I came up with felt too arbitrary. One day I was cataloguing my CDs, including the barcodes with the reference info, and it just struck me, looking at the numbers. I have a great affection for ancient Chinese and Japanese poetry, and it occurred to me that I could use barcodes to compose poems similar in length to the traditional Chinese Lu Shih, which seemed an interesting “translation” of method. Ancient Chinese poetry, in meter, syllable and rhyme, is tightly structured, none of which translates to English. The translator has to compose a new poem that evokes the original. I grew up in the 20th Century with free verse, without allegiance to traditional forms. So here was a way to impose a structure that varied, and incorporate an element that wasn’t internally generated.

Anyway I tried it and for me it worked. A lot of my early attempts were kind of self-absorbed. Eventually I adopted the practice of using the barcodes from CDs to compose poems inspired by the music on the recordings. One of my favorites, and one of the very few I have memorized – I do not posses my father’s gift for memorizing – responds to Prokofiev’s first piano sonata:

in the middle of the stars

is where the stairs come into being

spilling down

before anything is understood

the lake lies quiet

the sleigh ploughs up the road

the flushed descent meets lips

so close that skin achieves

a texture joined to the moment

when storms pass muster

& mongrels worry the bones of children

one night to hold advance at bay

one night to know that touch

abides

in the heart of the story

I also composed a lot using Zip Codes and Area Codes, which yield haiku and tanka-like verses. Slack Buddha Press published a chapbook of my ZIP Code poems. And then I went completely nuts and came up with sampling procedures to extract lines from books for aleatoric poems structured by the books’ ISBN numbers. That is waaaay too involved to go into.

CM: What first drew you to poetry and what prompted the shift to short stories and longer pieces of work? Do you ever miss writing poems?

SV: I grew up loving the poetry my father loved – Kipling and Robert Service, et al. I didn’t think about writing poetry, though, until I was sent to boarding school. I was a very insecure kid. My parents fought a lot, mostly because my dad came back from the war drinking hard, like a lot of men. He gave it up later but at that time it still created a lot of friction. My sister got married and moved out, my brother went away to college, and I was left alone with my parents. They needed some time to sort themselves out, so they sent me to a boy’s school run by Benedictine monks. It was awful. I got bullied mercilessly. Some of those monks had no business looking after kids. You mistreat a child in front of me, you’re gonna get it.

My one sanctuary was a creative writing class. I loved that teacher. How the hell he wound up teaching there I’ll never know, but thank God he did. He’d have students over to his home, and he and his wife were just brilliant at making you feel safe and accepted. I think they were hippies at heart. He introduced me to free verse, and I wrapped my arms around it and held on for dear life. The idea that a group of words – something I expressed – could achieve the status of art just because I said so, that there was a way that I could express my thoughts and feelings that had value and dignity, was very, very important to me. I built myself a shelter out of words.

But I’ve always loved stories more than poems. That was always my first desire, to write stories. I do miss writing poetry. Every so often I produce a verse or two. I’d like to get back to it at some point.

CM: Can you talk about the experience of being published? What has surprised you about the experience? What is something you think writers often believe about being published that isn’t necessarily true?

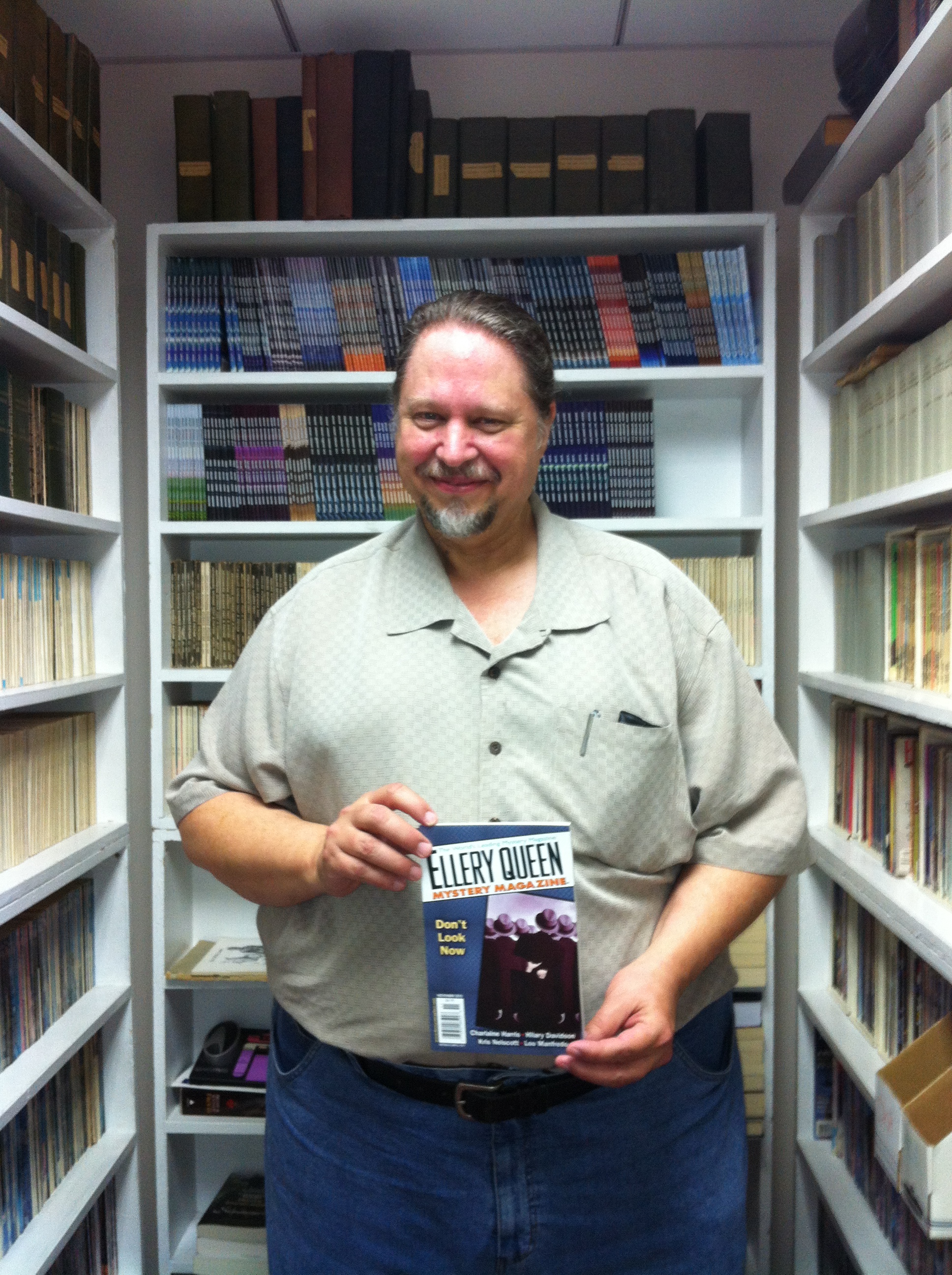

SV: The breakthrough for me was having a story accepted by Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. The editor, Janet Hutchings, is a living treasure. My story “Doloroso” was nominated for a Thriller award – that was a surprise. It was an important experience for the obvious reason that it validated my aspirations. And then “The Butcher of Gad Street” was published by Grey Matter Press, a press with very high standards, and I felt like things were going somewhere. At some point publication is essential if you’re going to keep doing it.

That being said, I’m not a great fan of self-publishing. I think it can work if you’ve developed your skills and already have a following. (Leaving book art out of it because that’s its own thing.) But if you have no prior publication credits, you get more credibility from someone else publishing you than you do publishing yourself.

But, you know, I’m sixty-two and I just have my second book coming out this year. I’m no raging success that anyone should swallow whole anything I have to say about it. Getting published, however you do it, is no guarantee of anything. There’s so much being published it’s staggering. It’s a tough gig. Whatever works for you, do that.

CM: How has it been working with Muse Harbor Publishing?

SV: Wonderful. Dave and Eileen Workman and Ian Wood gave me a tremendous gift. I think it helped that they’re all writers, too. Eileen is a philosophical essayist, and Dave writes thrillers. Ian writes everything, and like me is a visual artist too. They let me influence all aspects of the presentation of the book. I got to pick the font and have a say in the page design. They paid for those wonderful illustrations by Alan M. Clark, Steven Gilberts and Cheryl Owen-Wilson. They used my art on the cover. Even though they were skeptical about not having any text on the front cover they let me have it that way. They respected my wishes at every turn, and gave me the book I wanted. I wish that experience for every writer. I don’t know if I’ll ever have it again.

The book wouldn’t have come into being without Ian. He’s a brilliant writer, artist and musician – one of the smartest people I’ve known in my life. He dogged me to give him something to publish. I was reluctant because I wanted a big publisher. I’m not sure how long it took me to get past that, but he kept after me. I can be an idiot. Here are some people who respect and appreciate my work and want to publish it – why the hell am I saying no? It is incredibly affirming to hold a published volume of your own work in your hands. And such a volume! Childhood dream come true.

I have to take a moment to mention a book Ian recently published, Words on Torn Paper. It’s a collection of images with text in an artist book format – meaning the book itself is a work of art, all aspects of design, image and content meticulously considered and integrated. It is a poignant, searching, unflinchingly honest, beautiful and deeply moving work.

CM: You seem entirely comfortable writing across several genres. Have you always been drawn to science fiction, horror, and dark fantasy? What interests you about each of these genres?

SV: I think fantasy must have hooked me first. Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Alice in Wonderland, The Wind in the Willows. Probably mystery next – I was a big fan of Nancy Drew. Then horror – Edgar Allen Poe, Mary Shelly, et al. I don’t really think about what genre I’m writing in. I write the next story that comes to me. A lot of the stories I write don’t fit readily into one slot or another. I have a penchant for the weird and fantastic so there’s generally an element of that in there somewhere. Science Fiction gave me a hopeful view of humanity’s future in my youth and I’ve never lost that. I want us to travel to the stars.

CM: In your novella The Mountain & The Vortex, we visit a variety of vivid worlds and characters. What would you say connects them?

SV: Love and selflessness. They’re all trying to make their worlds better without seeking recognition for themselves. That’s going on around us all the time, invisible people trying to solve problems, make things better.

CM: In your story “Lighter Than Air,” which won the Best Fiction Award at the Santa Barbara Writers Conference, Lester Gill makes a conscious decision to forgive, and experiences clarity through a forgiveness that seeped “into his bones.” Have you found that this is an important exercise in life? How important is forgiveness?

SV: To me very important. Hatred, hanging onto grievances, however justified, makes people sick. I’m not perfect; I can be resentful. I don’t like people sticking their hands in my business. My mistakes are mine to make, thank you very much. And I don’t think being forgiving is the same as being passive. Come at me and I’ll defend myself. But I do my best to let go of resentments and injuries. Without exception. Forgiving myself has been hard sometimes. I’ve failed a lot of people. The Dali Llama said something interesting. Paraphrasing, here, he said, if you’re having a problem with someone, see them as a part of yourself, and it will calm you and restore your self-confidence. That’s a thought worth reflecting on.

CM: “The Burning Professor” moved me to tears. Can you talk about the danger of a “life spent in disguise?”

SV: You give me the greatest compliment with your tears a writer can receive. I think the danger lies in never being able to trust anyone. I wrote that story as an homage to women I’ve known who broke the glass ceiling at great cost to themselves. But I can connect with that struggle in myself. I’ve had a lot of cynicism around me in my life. A lot of my friends have very dark views of humanity that I don’t share. I also have friends and family who are religious in ways that I’m not. I have friends who are liberal and friends who are conservative, and I don’t believe in sides. So there have been a lot of times in my life when I’ve kept quiet.

I connect with it, too, in that I’ve never married and live alone.

CM: Chris Wozney recently penned a brilliant review of your book, which people can check out at The Nameless Zine. She’s an eloquent writer and clearly thinks a lot of your work. What was your reaction to her review?

Shock. I never expected to read something like that about my work. I’m still in shock.

In a very pleasant subsequent development, Chris has recently functioned as my editor. She helped me with my novel that is coming out next month, and was just brilliant. Her command of literature of all periods and genres is amazing. She has the capacity to get inside of a story and be true to the author’s voice. I would recommend her as an editor to anyone.

CM: Do you have a favorite story from this collection?

SV: “The Fourth Seven.” Earl is my favorite character in the book. He stumbles into his own better nature in spite of himself.

CM: What do you hope that readers will take away from your book?

SV: I’d like them to be heartened, overall. Some of the stories are horrific and very dark, but I don’t think the collection is dark as a whole.

CM: The artwork in The Mountain & The Vortex is really wonderful. Did you always have a sense of the pieces you wanted for this book?

SV: I wanted an image for every story, and four or five for the novella. For the most part I gave the artists free rein. I wanted to see what they would come up with, and I’m glad I took that approach. It was a sheer delight to see their pictures come in. I asked for amendments to a couple of them and the artists were very accommodating. Although at one point Alan Clark told me I was being a hard ass, so maybe I was less flexible than I imagined.

Alan’s a friend of mine. He’s a great writer too. He’s written a series of novels about Jack the Ripper’s victims that I highly recommend.

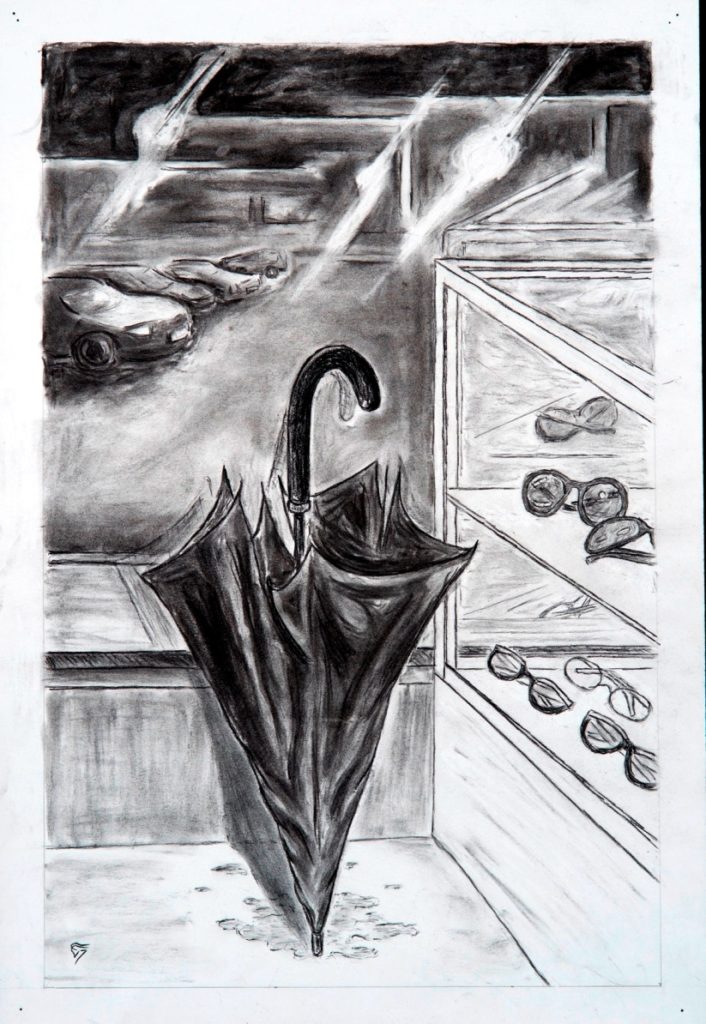

CM: You are a man of many talents. Some of the illustrations in The Mountain & The Vortex are your own creations. Please share a little bit about how you approached the art for The Mountain & The Vortex and how you got started with your ballpoint pen drawings.

SV: Well, I have a fondness for the design aesthetic of Alvin Lustig, who did covers for New Directions in the forties and fifties, and also for some of the sparser SF covers through the sixties. I like covers that evoke the gestalt of a book without telling you what it’s about. One of my favorites is the first edition of The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch by Philip K. Dick. That cover is so simple but very effective – you see it and it stays with you. It has a stylized hand with an eye in its palm on a black background. So I was shooting for something like that, which actually became the back of the book. I did several drawings, fiddling around with triangles representing mountain and vortex, and the strongest one wound up on the front. I’d expected us to use just one of my images but we wound up using two. I couldn’t see any way to make text work on the front that didn’t compromise the image, so I suggested we leave the front cover text free. The publishers, God love ‘em, went along.

The frontispiece I drew in about a hot minute. I can’t remember exactly the sequence of events that led to that. I just remember that we needed an image now, and the idea popped in my head. And I just did it, bang. Ian had played around with making negative images of some of my pen drawings, and I liked that, and suggested we do that with the frontispiece.

I also wound up doing an illustration for one of the stories. At the last minute I decided to include “The Alchemist’s Eyeglasses,” which I’d thought didn’t fit with the other stories, but changed my mind. It was too late to ask one of the other artists to do an illustration for it, so I did one. I hadn’t worked with charcoals in a long time but it came back to me. I very much like having an umbrella at the proximal center of the book.

CM: Do you find that your drawings inform your writing and vice versa?

SV: Less inform than support. When I draw I get to let go of thinking. The writing doesn’t feed the drawing, it necessitates it. The drawing recharges my batteries.

CM: Your recent show in Chelsea was your first solo exhibition in more than 20 years. How have you evolved as an artist in that time?

SV: Until a couple of years ago I went fallow as a visual artist. I went broke and had to move, trashed a bunch of my art and supplies. In my new place there’s no room for a studio. I very nearly gave up making art altogether.

Evidently I just couldn’t. There’s no place to paint in my apartment. Doing that drawing for The Alchemist’s Eyeglasses, I got charcoal dust all over the living room floor. One day it occurred to me I could just draw with the same pen I write with, and that evolved into five hundred plus drawings.

I think what’s different for me now, making art, is that I trust myself more than I used to. I’m more willing to follow my instincts.

CM: Where can people view your ballpoint pen drawings? Are they available for purchase?

SV: Right now just on my website. I’m in the process of getting representation by a gallery in Helsinki. When I get some breathing space I’ll look for a gallery in Los Angeles. Although I might just represent myself online. I’m still working it out.

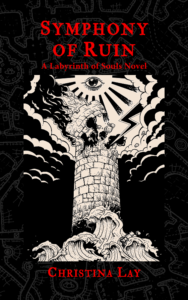

CM: You’ll be attending the World Fantasy Convention in San Antonio, Texas in November. I understand you and a group of writers will be launching a series of books there. Could you talk a little bit about that project?

SV: With pleasure. It’s a series of books that share the theme, Labyrinth of Souls. The idea came from Elizabeth Engstrom, who has been my mentor and friend for many years. I met Liz through John Reed, when the two conducted a writing seminar in Zihuatanejo, Mexico. Through Liz I connected with a wonderful circle of writers at retreats she held in Eugene, Oregon. One of the regular attendees to those retreats, Matthew Lowes, created a role-playing game called Dungeon Solitaire, and collaborated with an artist in Germany to design a set of Tarot cards specifically for the game. The art on the cards is just beautiful. Liz had the idea that we could write short novels with a shared theme, and use the images from the cards as cover art for the books. She floated the idea by ShadowSpinners Press, and they bit, so we were a go.

Those of us participating each picked a card that somehow evoked what we had in mind to write, and from there had free rein to do whatever we wanted, so long as the Labyrinth of Souls theme, and some sort of Tarot association, were incorporated in the story. That’s a wonderful way to work. To have full latitude like that, and know you’re working in concert with other writers, blind to what each other are doing, generates a sense of camaraderie. Writing is such a solitary endeavor, that’s a gift. I’m enormously grateful to have been invited to participate.

Four novels in the series have been released so far: Benediction Denied, by Liz; Symphony of Ruin, by Christina Lay; Littlest Death by Eric M. Witchey; and The End of All Things, by Matt. My book, The Door of Tireless Pursuit, is in the pipe, so we’ll be launching at least five at the conference. More in the series are forthcoming from John R. Reed, Cindy Ray, Cheryl Owen-Wilson (who contributed two illustrations to my story collection), Pamela Herber, Aliexis Duran and Mary Lowd. This is a brilliant group of writers. I’m proud to be included with them.

CM: Anyone who follows you on Facebook will know of your passion for classical music. You often share informative posts about little known composers. You’ve become involved, now, with a project related to that. What has that been like for you?

SV: Wonderful and frustrating. I haven’t been able to devote much time to it, and I want to do more. The people connected with the project are extraordinary. We all know we’re in it for the long haul. It arose out of the connection I mentioned that I made on Facebook with the pianist Arsintey Kharitonov. That aspect of it has been very gratifying. There aren’t many people I know who have broad knowledge of classical music. Meeting Robert Olen Butler was a godsend because he shares that enthusiasm. Arsintey not only has that knowledge, he performs it. I was ecstatic to connect with him. Having an opportunity to share my knowledge in a broader way is like relieving a constricted muscle.

CM: Please tell us about your new position with Masterpiece Finder. What do you hope to bring to the website? Where can we learn more?

SV: I’m a contributor and editor. I’m also the communications director. Which means I’ll be reaching out to composers and musicians, coordinating interviews and informative pieces for the website. Eventually I think we’d all like to branch out in a more direct way, and facilitate performances and recordings. One of the things I want to do this year is interview musicians in the L.A. area, and promote more diverse concert programs. There are thousands of composers, from Bach’s time to the present, whose work rarely or never gets performed. And it’s a pity, because that reservoir is deep and wonderful. I could blow your hair back for months on end with works you’ve never heard or even knew existed.

To learn more go to the website: http://www.masterpiecefinder.com/.

CM: What advice would you give to a writer who is just starting out?

SV: Learn how to manage your time so you don’t go crazy. There’s a lot of hidden stress in the arts. However much it gets romanticized in film, there’s no way to see it from the outside. Because it’s days and months and years lived a minute at a time. I say this as someone who has not mastered this aspect of the life. I pull too many all-nighters and I’ve dropped a lot of balls. Pace yourself. When things start moving for you people are going to want things from you and you have to show up. However long you think it will take you to do something, triple that. Quadruple it. If you come in under that mark you’ve done well.

If you miss a day writing it may take around two weeks for you to get back into the flow of it. It takes about thirty days to establish a habit.

And then believe in yourself and tell a good story. What you have to say will take care of itself. Just tell a good story. Love words. Read inside and outside of your comfort zone.

CM: What lessons do you feel you were meant to learn before arriving at this special and significant point in your life?

SV: Do it now and show up. The one thing I can be sure my mind won’t retain is an idea I ignore. Other people’s opinions of me are none of my business. Let go of resentments and don’t dwell too much on the past.

Be grateful. Be grateful for the people around me who support me and believe in me. Be grateful for whatever I have to work with. A lot of parts of the world I could throw a rock backwards and hit someone who’d give an arm and a leg to have my problems. I’m especially grateful to have learned how I do this work and still have the ability to do it.

Cultivate a supportive inner voice. Self-criticism, beyond recognizing something I could have done differently or didn’t understand, is rarely, if ever, productive.

CM: What are you working on now?

SV: I’m writing stories every day, and gearing up for my next novel. I have several novels in mind and I need to pick one. I’m writing essays for Masterpiece Finder. I’m focused on getting the business end of my affairs in order. That’s become critical. I need to put what I’ve learned to fuller use.

SV: Any final thoughts you’d like to share?

Just to thank you for being so supportive and appreciative of my work. I want to say again that helping you with your coloring book journals has been one of the great joys of my life. You make the observation in your introduction to them that people who have traumatic experiences often engage in artistic practices of some kind to support their recovery processes. Exploring the lives of all these lesser known and forgotten composers that I have, whose lives span three hundred plus years, the vast majority of them knew great hardship. It is unquestionable that hardship informed and fueled their motivations to keep composing. Charles Tournemire, for example, began his Sixth Symphony, was conscripted and survived the Battle of Verdun, then returned home to finish the symphony. The alchemical power of creativity to translate pain into beauty is one of the most remarkable things about humanity. Giving people a way to access that, in the sensitive and insightful way that you have, is a tremendous contribution. I’m very proud of the small part I was privileged to play in that. Hand to heart, thank you.

—

To learn more about Stephen T. Vessels, please visit Stephen’s website.

You can purchase a copy of The Mountain & The Vortex and Other Tales on Amazon.

You can find Stephen’s other stories on his Amazon Author Page.

PLEASE NOTE: The opinions, representations, and statements made in response to questions asked as part of this interview are strictly those of the interviewee and not of Chloé McFeters or Tortoise and Finch Productions, LLC as a whole.

2 thoughts on “Stephen T. Vessels”

Wow. Tour de force. VOICE!

One of the most generous and passionate souls I have had the pleasure of calling friend. Rest In Peace Stephen, or shake the walls of Heaven. If anyone can, it’s you, sweet friend.