It is my sincere pleasure to share this interview with Dr. Rochelle S. Cohen, author of the recently released poetry book Ode for the Time Being. Dr. Cohen was born in Brooklyn, New York. She is presently Professor Emerita at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where she was the recipient of the 2008 College of Medicine at Chicago Distinguished Faculty Award. She is a neuroscientist with publications in synaptic structure and biochemistry and hormonal effects on brain and behavior. She was recently Guest Associate Co-Editor with Dr. Alberto Rasia-Filho and Dr. Oliver von Bohlen of a Special Issue and e-book of Frontiers in Psychiatry: Frontiers in Synaptic Plasticity: Dendritic Spines, Circuitry and Behavior.

The poems in Ode for the Time Being reflect Dr. Cohen’s lifelong passion for marine life and science, as well as her deep love for her late husband, the writer and artist Rex Sexton.

I loved this collection and was honored to be able to learn more about the brilliant, curious, and playful mind behind the poems it contains. I hope you enjoy our conversation.

——

CM: I know you grew up in Brooklyn with your parents and sister. Brooklyn has such a rich and distinct culture. What are some of your best memories of that part of New York City?

RC: My best memories are those of family and friends and the warmth of the people. My family is close knit and the relationships with extended family were seamless. Growing up in a city, just a subway ride into Manhattan, was important for my outlook.

My family lived in the Glenwood Projects in the Flatbush area of Brooklyn. The housing was built for men and their families after World War II. There were thirty families in each building of which there were many. Consequently, there was never a dearth of friends. We put on shows for our parents, played “skelly,” a chalk game on the sidewalk with bottle caps, and hopscotch.

I went to Samuel J. Tilden High School in Brooklyn. There were approximately 5,000 students at any one time. There were inspiring teachers and many opportunities to express oneself. I loved Drama Class and Drama Club. The school put on Broadway shows and one could participate in any way. We, also, had grand productions called “Sings.” I participated in lyric writing for one year. Since there were so many students in each class level, there were grand choruses with magnificent songs emanating from them.

My very favorite memory is when my mother took me into Manhattan in the winter and bought me a bag of hot chestnuts from a vendor on the street. When we arrived back in Brooklyn, we stopped at a knish store and ordered hot knishes.

CM: As a young girl, you were involved in dance. What do you remember about those early lessons and your first exposure(s) to the arts?

RC: My mother wanted me to be a dancer. However, it did not suit me. I am not athletic. She took me to The June Taylor School of the Dance in Manhattan every Saturday, My parents and sister Marion would watch me. The ballet teacher was French and very strict. I loved tap dancing, but modern dance was too athletic for me. I quit. My mother said that I would regret it and, indeed, it was one of the biggest regrets of my life. But, it stuck and I love dance more than any of the arts. My favorite dance group is The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. When I was a postdoctoral fellow in Manhattan, I would go to the Alvin Ailey dance studio to take lessons for non-dancers. It was an exhilarating experience with live music.

My mother and father loved Manhattan. I deeply appreciate that they took me there a lot so that I could see something larger than myself. In grade school, we went on field trips to museums. The teachers, themselves, were very talented in the arts and inspired us to create. I still have a pouch that I made in third grade.

CM: How did you first come to love words and books? Did you read and write poetry as a child? Who were the poets who first spoke to you?

RC: My father influenced me to love words and books and learning, in general. Every night, he read The New York Times and my sister Marion and I caught the habit. My father bought me a Roget’s International Thesaurus when I was about 17 years old. I still use it and prefer it over the computer thesaurus. The pages are worn and folded and bookmarked with old pieces of paper, but I love it.

I remember writing poems as a child. I loved lyrics to Broadway musicals. I wrote song lyrics for a young group and also productions in high school, as noted above. A secret dream for me was to become a lyricist.

The first poet I loved was John Milton, whose poems I read in college. I can never forget the lines from “Samson Agonistes,” where Samson lamented on his blindness:

“O dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon,

Irrecoverably dark, total eclipse

Without all hope of day!”

I still have my English book, Major British Writers from 1963. I, also, loved French medieval poetry, that I read in my first year of college in French class.

CM: In college you studied Biology. Had that always been your intention? How did you first become interested in that field of study?

RC: My first intention in college was to study French. But, at Hunter College in Manhattan, they said that if you have any intention of choosing Biology as a major, you needed to start right away to ensure that you would have the appropriate prerequisites, like chemistry and physics, to proceed in a timely manner. So, I went into Biology, but still took French. Biology won my heart in the end. I had a marvelous professor and decided I wanted to be like him, teach and capture the attention of students. I loved being in the laboratory and looking in the microscope. It was another world. I liked doing this by myself, the solitary nature of the work. I still love languages, though, and in retirement, I am taking Brazilian Portuguese lessons with a professor from Rio de Janeiro on Skype.

“I loved being in the laboratory and looking in the microscope. It was another world. I liked doing this by myself, the solitary nature of the work.”

Dr. Rochelle Cohen

CM: Some years later, you earned a Master’s Degree and a PhD in Physiology and began your postdoctoral training at The Rockefeller University in New York. What can you tell us about that time in your life and the work you were engaged with there?

RC: The three years I spent at The Rockefeller University in Manhattan was the best time of my life. As a postdoctoral fellow, one’s sole responsibility is research. There are no committees or other distractions. The Rockefeller University is a very special place. I was honored and most fortunate to work with Dr. Philip Siekevitz, a giant in the field of Cell Biology and Neuroscience. Dr. Siekevitz was extraordinarily kind. He, also, made me love words. When we wrote scientific papers, he and I would sit in his office and write every word together.

In the lab, we isolated parts of synapses, called postsynaptic densities. These are very dense structures behind synaptic membranes. Although, the precise function of these structures is still unknown, they contain an array of molecules that are important in nerve transmission and have been implicated in behaviors, including memory.

Scientists from all over the world came to study at Rockefeller. The entire experience broadened my personal and professional perspective.

CM: You also spent time in the Netherlands. How were you spending your days there and how did your experiences help to further shape your views of the world?

RC: My days there were spent in The Rudolf Magnus Institute in Utrecht. This institute is world renowned for neuroscience and it was a pioneer in the field of neuropeptides and behavior. Specifically, I worked in the laboratory of Dr. E. Ronald de Kloet. Dr. de Kloet is an eminent scientist in the study of stress hormones, which receives tremendous attention nowadays. Years ago, biologists did not approach questions of behavior, as it was difficult to quantify. Now, there are behavioral models, which allow this kind of quantification. The experiences in the Institute made me appreciate this approach and, eventually, I added it to my own research on estrogen effects on the brain and behavior, specifically, female reproductive behavior and anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors.

The scientists at the Institute were incredibly kind and I made friends for life. Every week-end, someone took me to another part of The Netherlands and all invited me into their homes. I was a stranger, but they completely welcomed me. I keep that in mind all of the time, towards people, who are visitors or new to this country. Being on my own and away from home made me see things differently. It was an unforgettable personal and professional experience.

Below is a picture of a watercolor painting of my favorite canal spot in Utrecht. I would sit in a cafe across from the one depicted in the painting and have a coffee. I bought the painting in an art gallery along the canal. It is one of my most precious memories and souvenirs of that place and time.

I, also, spent two summers at the Friedreich Miescher Institute in Basel, Switzerland, working in the laboratory of the eminent neuroscientist Dr. Andrew Matus. It was a thrill to travel to the Alps during my free time. Years later, Rex, Marion and I returned to Grindelwald, a breathtaking experience.

CM: You enjoyed a thirty-year career at the University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Medicine, which involved researching the structure and biochemistry of synapses and hormone effects on the brain and behavior, as you mentioned. What are some of the most surprising things you’ve come to understand about how our hormones affect our minds, moods, and actions?

RC: The most startling thing I learned is how much our behavior is dictated by hormones. I worked with both estrogen effects on rodent reproductive behavior and anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors. A tiny amount of a specific hormone can completely alter a specific behavior. Another outcome of our findings was that these particular behaviors appear to be dose and time sensitive to estrogen, for example, in order to affect behavior.

CM: You were also a professor and advisor, teaching a range of courses, including Neuroendocrinology of Birdsong, which sounds fascinating. What is that? What would you say was the most rewarding part of your teaching career? What important lessons did you learn from your students?

RC: I loved giving the lecture on the Neuroendocrinolgy of Birdsong. This subject is about how hormones affect brain areas which, in turn, lead to birds singing. In general, males sing and females do not, with some exceptions. Zebra finches are examples of birds used to study the song system. In general, the brains of male songbirds have brain areas, which are not included in the brain of female birds. So, this is an example of sexual dimorphism of the brain. Each male has a single song type uttered in a reproductive context to attract females and repel males. Birdsong can be quite complex, as reflected in sonograms, measurements of various qualities of song. Birds learn songs from their fathers or tutors, so this field of neuroscience tells us a lot about learning and memory, in general.

The most rewarding part of my career was watching my PhD students at their thesis defense. Working toward a doctorate is difficult, with long hours into the night, experiments that may or may not work, deadlines for grants and conferences. It usually takes five years or so in the biomedical sciences. But, to see the students at their thesis defense, well, there is nothing like it. They were so articulate and poised and knowledgeable about their field of study. They had total command of the subject matter and audience. They “take over” the room, so sophisticated and advanced. It was a thrill, the very best part of my career.

The students taught me very much. They were so dedicated and persevered and worked very hard, often late into the night. They always had a good attitude, irrespective of the difficulties. Their excitement for science was contagious, their thinking original. The students taught me more than I taught them.

I remain in contact with virtually all of my PhD students. To see them succeed in life and in their careers is extraordinarily satisfying. They are researchers, physician scientists, physicians and educators. I am so proud of them and it is the greatest pleasure to see how wonderful their lives unfolded.

CM: You’ve spoken about how you see science as a form of art. I’d love to hear more about that. When and how do you think you first came to see it that way? What do you find most elegant and artful about science?

RC: My first thoughts about science as a form of art came from philosophy and aesthetics. There is so much external beauty in all life forms. As I studied more, I saw the beauty of molecules, like DNA. Can you imagine only four bases form an unimaginable and incredible amount of diversity? When I was younger, I likened it to a symphony with only a few basic notes forming a complex piece of music. What I find elegant and artful now, is the utter harmony of life processes. Hormones are the most elegant molecules. They virtually control all processes in various ways, creating the balance we need to live and survive. It is, indeed, like a symphony.

“What I find elegant and artful now, is the utter harmony of life processes. Hormones are the most elegant molecules. They virtually control all processes in various ways, creating the balance we need to live and survive. It is, indeed, like a symphony.”

Dr. Rochelle Cohen

CM: As an electron microscopist, you were able to see and capture images of the inner architecture of the brain, which I would imagine affords one a very unique perspective. When you were photographing subjects, were you conscious of aesthetic effect? If so, did your considerations and the resulting images cause you to appreciate your photographs and work in unexpected ways?

RC: We have to report the actuality of the findings. However, I learned that composition of the photograph is very important, not only for the aesthetic effect but, mainly, to the understanding of the findings, the data. I learned to be a good photographer and to compose and present the picture, at the same time revealing the reality of the finding. Taking the photograph through the electron microscope has particular requirements, itself, in terms of detailed focus, for example, that add to the aesthetic of the final image. An electron microscopist has “exceptional” eyes and sees structures that others, who do not have an eye for detail, may miss. It is, indeed, a special kind of science and art. Some of my images have been able to be used more than once, as they are kind of “classic” images. That was unexpected!

CM: Your poems have been published in The Avocet, PoetsWest, Lone Stars, and elsewhere. When did you first begin submitting your poetry for publication? What did it feel like to have your first poem published?

RC: It is only recently that I began submitting my poetry for publication. Not being formally trained in poetry made me quite intimidated to submit. Because my late husband Rex Sexton was a poet, I read a lot of his journals and came to understand how the field worked. I was very thrilled to have my first poem published. It makes me feel alive, now that I am retired.

CM: Your new collection, titled Ode for the Time Being, unfolds in several sections, including one section called “Poetry in Ocean.” The poems in that section explore the wonders of marine life and science, which you are obviously passionate about. I know that you spent five summers at The Marine Biological Institute in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Were the poems in “Poetry in Ocean” inspired by your time there?

RC: Some of the poems were definitely inspired by my time at the Marine Biological Laboratory. That is a very special place with devoted and remarkable scientists, who solve important and basic scientific problems by their observations in marine animals.

However, I, always, loved marine animals. My family spent summers at Rockaway Beach in New York when I was a child and that may have been the beginning of my love for the ocean and its inhabitants. Marine animals are related to the aesthetic question above. They are formed perfectly to meet the challenges that they face, be it, a limpet, who adheres tenaciously to rocks and must bear the force of crushing waves, or animals living in the hydrothermal vent, who face incredible challenges of crushing pressure and extraordinarily high temperatures.

CM: Tell us about the fish Tiktaalik and what inspired you to write the poem “Moving On.”

RC: I was entranced by this “fishapod,” a 375 million year old fossil fish. The fossil was discovered in the Canadian Artic in 2004 by Neil Shuban, Ted Daeschler and Farish Jenkins. It was really a fish, but it had the head of a crocodile and unusual fins. Imagine one of the first to decide to come onto land. The start of something big!

CM: I think you have a fantastic sense of humor, Rochelle, and that shines forth in your poetry. More than a few of your poems in “Poetry in Ocean” are funny! I laughed out loud at “Temptacles” and “Slings and Arrows.” And one of my favorite poems in the book has to be “Mustang Sally.” I thought it was brilliant.

For me, that section of poems spoke to your deep sense of appreciation and curiosity. Do you have a favorite marine animal and why?

RC: I always loved marine animals and invertebrates. Again, I go back to my time at Hunter College, where I took a course in Invertebrate Zoology. So much diversity in the ocean teeming with life.

My very favorite marine animal is the builder of sandcastles, the tube worm. Some of these kinds of worms build a special tube around themselves, which projects from the seabed. The tube may be made up of large sand grains or secreted and foreign material, like shell fragments. A string of mucus and sand grains cement the sand grains into a mosaic towering fort for protection from predators. Some of these tube worms are very beautiful, like the fan worm Sabella. These tube worms have a beautiful crown, a small extension at the front of the mouth, at the top. For me, they are the “architects” of the ocean.

Another favorite is the axolotl, who lives in brackish water. They are vertebrates, amphibians, who retain their neonatal form throughout life, kind of the Peter Pan of the amphibians. They are different, with gills outside instead of in. And, what an expression! They make one smile. And, such a funny name. I can not leave out sea turtles. They leave home and travel across thousands of miles of oceans. Then they use magnetic fields to return to their place of birth, the same beach, to nest.

CM: What do you wish more people understood about our “aquatic ancestors”?

RC: I wish that they could understand their internal, as well as external, beauty, the mechanisms that they use to survive. And, their necessity for the chain of life. Without them, I doubt we can persist. What is happening to our oceans is tragic. Today, I had a Brazilian Portuguese lesson. My professor is looking for an apartment and she showed me one that she was interested in. She showed me the map of the neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro. I said: Look! It’s only a few blocks away from the beach. But she replied, that that particular beach was polluted. How very sad!!!

Pictures on the internet of sea animals tangled up in strings or their digestive system filled with plastic are heart breaking.

CM: What can you share with us about your poem “Noah”?

RC: Noah Cohen was my father. When he passed away, the Rabbi asked me sort of the same question, i. e., what can you tell me about your father? I replied that he taught me everything I know. The Rabbi said, no, he taught you to love learning.

Noah cared about humanity. He deeply felt that we should help people. He worked for the Federal Government and that is why I framed the poem the way I did, about various important government agencies. I wrote it around the time of Hurricane Katrina, so the image of Noah’s Ark, the storm, the floods, and FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) and other government agencies sparked the poem.

CM: What inspired the poems in the section titled “Discoveries”?

RC: I am always astounded when I read about a scientific discovery. For example, I was thrilled when I read about the detection of gravitational waves resulting from the collision of two black holes that occurred billions of years ago by the LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) team. They invented a tool that can detect gravitational waves generated by cataclysmic events in the universe. There are two detectors, one in Louisiana and one in Washington, and they measure ripples in the fabric of space time, gravitational waves. These ripples arrive at earth from a huge event in the far away universe.

CM: The book contains a poem titled “By the Light of the Moon,” which is your poetic interpretation of a Brazilian legend, and another poem, “Peixes no Carnaval” (Fish at Carnival), is written in both Brazilian Portuguese and its English translation.

I love languages and I find Brazilian Portuguese to be such a beautiful language to hear spoken. When and how did you first learn Brazilian Portuguese and what first appealed to you about the language, legends, and culture?

RC: I learned to love Brazilian Portuguese when I was eighteen years old and I saw the famous Brazilian composer and singer Antonio Carlos Jobim on television playing the guitar and singing. I was mesmerized by the beautiful language and the bossa nova sound. I have, also, always, loved Latin American authors, including Nobelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez and the great Brazilian writer Jorge Amado. I love the genre of magic realism and that is part of why I love legends.

When I retired, I wanted to go back to my love of languages and I selected Brazilian Portuguese. Another wonderful experience that led to my choice was that at the time, I was collaborating with the distinguished Brazilian scientist, Dr. Alberto Rasia-Filho. Knowing him long distance and becoming such close collaborators and friends was a sign for me to select that language.

I found a wonderful site on line, Verbal Planet, where you can learn a language with a tutor on Skype. I selected Professora Maria Eugenia Freitas, who lives in Rio de Janeiro. The lessons are tailored to my wishes and, in addition to doing exercises and readings in the workbook, we listen to music and I read a lot of Brazilian Portuguese novels, discovering fantastic new Brazilian music and writers along the way. Some of these writers include: Moacyr Scliar, Clarice Lispector and Noemi Jaffe. Eugenia is interested in film and I have seen a lot of Brazilian films. It is really an immersion into Brazilian culture.

The following is a translation of a poem I wrote in Portuguese upon the death of João Gilberto this past July. João Gilberto was a famous singer, songwriter and guitarist, who was a pioneer of bossa nova. It explains why I love the Brazilian Portuguese language and culture.

For João Gilberto

People always ask me

Why do you study Portuguese?

Why not French, Spanish,

Italian, even Mandarin Chinese

as everyone else does?But, they do not understand the secret

Dr. Rochelle S. Cohen

language of the samba and bossa nova

“Bim bom bim bim bom bim bim”

and the missing of the Brazilians for

the quiet soul of João Gilberto.

The friendship of Tom and Vinicius

with a glass of whiskey, while

they sing songs of love

and loss, the blossoming of a

a young girl on the beach of Ipanema.

The humor of Jorge Amado,

“Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands,”

the beauty of Gabriela, the aroma

of clove and cinnamon, a festival for

our senses, the magic of Bahia.

The intelligence and sophistication

of Clarice “The Hour of the Star,”

the warmth and humor of Moacyr,

who lives in my heart.

Noemi Jaffe, I look like her.

My colleague, friend and brother,

Alberto Rasia-Filho, Professor,

father of the marvelous Luís Afonso

and leader of spines in the amygdala,

whose kindness makes me smile.

The beautiful Eugênia, whose voice is as

lovely as a song by Jobim,

and who teaches me Portuguese words

which fill my heart and mind

with happiness.

CM: Ode for the Time Being opens with a profoundly moving section titled, “Missing Rex” and the poems you share there are about your beloved late husband, the acclaimed writer and artist Rex Sexton, whom you married in 1982. How did it feel, writing those poems, and what does it mean to you to be able to share those poems and reflections with others who might also be mourning the loss of their spouse or partner?

RC: It felt cathartic in a way. In Judaism, one says a special prayer called Kaddish when a family member passes away. I wrote “Winter of My Soul” in a taxi on my way to the synagogue to say the prayer. The entire poem came to me at once.

It means a lot to me to share these poems and a sense of grief. People, who are grieving are “lost” in a way and it is somewhat comforting to know that others feel the same way. Other poems may bring back good memories. This is exemplified in the poem “Ice Skating,” how Rex and I went to the elegant Pump Room in Chicago on a cold winter’s night. Writing about it makes the experience come alive again.

CM: Has grief taught you anything about creating, and if so, what? Has the act of creation been helpful in some way?

RC: I think with grief, one is more sensitive than usual to internal and external conditions, thereby, allowing some creative “juices” to flow. I remember feeling the oppressive humidity one day and when the cloudburst finally came, I felt relieved of the grief, as well as the closeness in the atmosphere, for a while. It stimulated me to write a poem about that feeling, “Steambath for Your Troubles.”

To an extent, the act of creation is helpful as a kind of catharsis and a way of making the lost person come alive again, albeit on paper.

CM: In your poem “Homecoming” you write about saudade, a Portuguese expression that has no exact English equivalent, but which, as I understand it, refers to a profound sense of longing and sadness, nostalgia, and the painful awareness of absence. I could feel your saudade for your late husband so palpably throughout “Missing Rex.” Your poem “Winter of My Soul,” which you mentioned, is so vulnerable and heartbreaking, it had me in tears. What you were able to capture so honestly is a gift.

I know that Rex also wrote poetry. What do you think he would say about Ode for the Time Being and do you think he’d be surprised by the poems you’ve written about him?

RC: “Saudade” is my favorite word in any language. It is powerful and expresses so much in one word. I think Rex would like the poem, as it truly captures how I felt when he passed away and still feel. The poem says that it is not the grand things that one misses, but the everyday experiences. I think that is the essence of the missing, the saudade.

On a humorous note, Rex liked when I wrote about him in my Brazilian Portuguese homework compositions. If you were with Rex, you could be sure an adventure was ahead. I used to read my compositions about these adventures to him in Portuguese for practice and then translate. Sometimes, instead, I would write about a classical Brazilian book I read or something not having to do with him. He would ask: “Where am I in this?”

Several of the marine poems I wrote when Rex was alive and he liked that and he was proud of me for writing and encouraged me to submit them to journals.

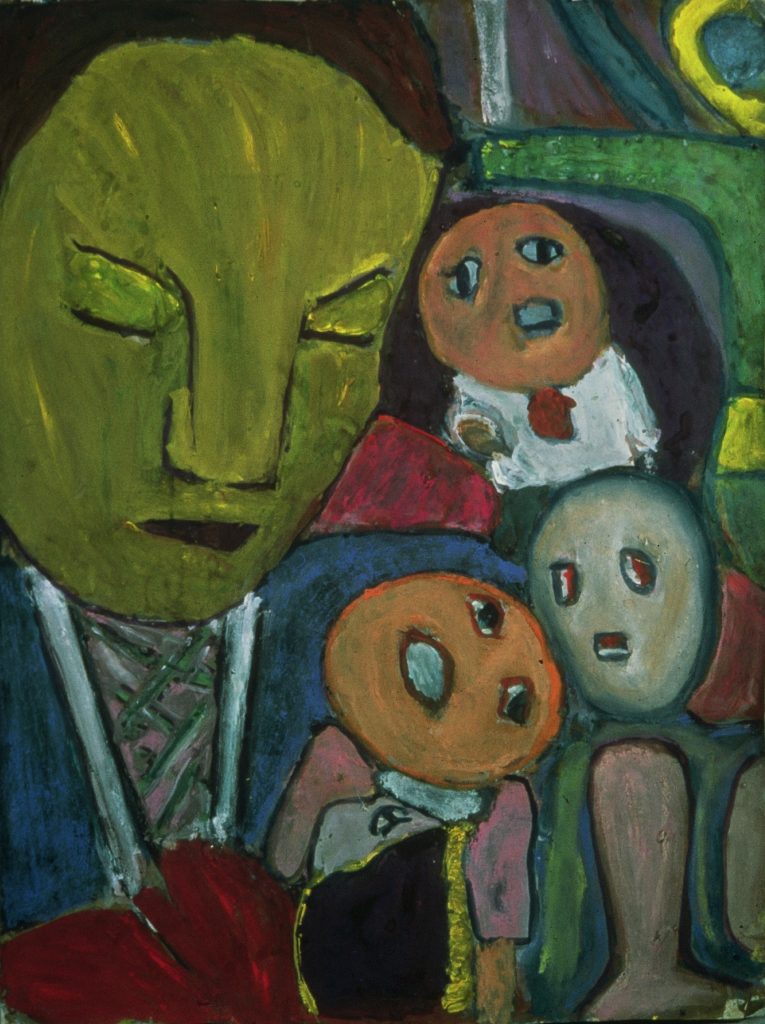

CM: The cover image for the book is actually one of Rex’s paintings. Was he already painting when you first met? What were your first impressions of his art?

RC: Rex was primarily a writer. I knew he wanted to paint, but it was just a gleam in his eye. I had gone to a conference in The Netherlands and brought him back a good paint and brush set from there as a souvenir. One day, a friend of his, who was an artist, visited us. Rex took out the box and they spent most of the time painting. Rex kept it up and before long, he had twenty paintings. He made slides of them and took the slides around to galleries in Chicago. I was shocked when he called me at work and told me that the second gallery in Chicago’s main art district that he went to gave him a one-person exhibition. It is very difficult and intimidating for artists to show their work to gallery owners and many great artists fear doing so. So, it was a wonderful surprise.

Rex had a “dark” way of looking at the world. His first paintings reflected that way of being and sometimes it was difficult for me to like the paintings. I, often, wondered exactly what he was thinking. But, as they sat in our living room, I got to understand and love them. Afterwards, his paintings got lighter in tone. But, they still reflected his fatalistic philosophy, that, in a sense, we are all puppets living in a predetermined world. That is why many of his figures are so doll-like. The following is one of his earlier paintings, “The Dollmaker,” exemplifying this vision.

CM: Were there things you appreciated about his work that he himself couldn’t see?

RC: Rex had a terrific sense of humor, which often emerged from his paintings unbeknownst to him. He was different, an outsider, someone looking in from the outside. He loved animals and many grace his paintings. He always exhibited at the animal shelter in Chicago in an international exhibition of animal art. One of the paintings is called “The Lady and the Tramp”. This is what I mean about being an outsider looking in. It is a universal feeling. Several people wanted to buy this painting. Everyone connected to the emotions emanating from it.

CM: One of your poems begins with the line, “He gave her wings, she gave him roots.” I thought that was lovely. How do you think your unique styles and worldviews informed and inspired one another, in life and in art?

RC: Rex and I were married 33 years and we definitely influenced each others’ thinking and being. As a scientist, I am very pragmatic. Scientists must follow strict rules, even though we may think creatively and “out of the box” in the confines of our work. We are, also, great believers of cause and effect.

Rex had a completely different way of looking at the world. As noted above, he had a fatalistic view of the world and thought that things were predetermined. This was difficult for me to reconcile with my own world view. But, eventually, I came around to his thinking a little and he appreciated my way.

Rex taught me so much about art. He always had great insights and we were immersed in the art world, always going to galleries and museums. His friends were writers and artists and they often were different in their thinking and ways of life than scientists. In this way, I saw a different way to be and think, which I appreciated. Essentially, Rex brought me back to my “center” after spending so much of my life in the sciences. He reminded me of the things that I describe above and love, literature, dance, poetry.

CM: In the poem “Homecoming,” you wrote about one of the sea turtles you mentioned earlier, one who has navigated thousands of miles across the ocean by “means still mysterious…” and in “I Hear a Symphony,” you refer to the “composer and conductor still unknown.” What fascinates you most, today, about the mysteries of life? Is there value in the mystery itself?

RC: For me, the mystery is everything. That is, in part, why being a scientist is such an amazing profession. There are mysteries wherever we look and we have the hunger to unravel them. I would imagine it is the same in any branch of science, especially, physics and math, to understand the universe, things bigger than ourselves. There is wonderment everywhere, whether it is in the behavior of a funny squirrel, creativity in the arts or when we look up at the stars. When we contemplate things beyond the mundane, I believe that we become better people and want to preserve nature and the better angels within ourselves.

“There is wonderment everywhere, whether it is in the behavior of a funny squirrel, creativity in the arts or when we look up at the stars. When we contemplate things beyond the mundane, I believe that we become better people and want to preserve nature and the better angels within ourselves.”

Dr. Rochelle Cohen

CM: You wrote about how that turtle was performing a ritual of her ancient ancestors. I love thinking about that. Are we so different, with our rituals and traditions? As a scientist, as a writer, as a woman, what do you believe about the significance of rituals in our lives? Do rituals play an important role in your own life, and if so, how?

RC: That is a marvelous question. I had not thought about that, so when I read the question a spark went off in my mind. No, we are not so different when one thinks about it. I love rituals and tradition. I am a scientist, but I strongly believe in many of the rituals and traditions of Judaism, even though some are inconsistent with scientific thinking. It is like a homecoming to our ancient ancestors.

I think these rituals impose order to our life. Whereas, many aspects of religion may be irrelevant or unbelievable to people, I like the order that some rituals impose. For me, a sense of order is important, whether it be in my work, ethics or daily life. As I scientist, I see order all around me, whether it be in the laws governing a tiny molecule or the universe.

I, also, feel strongly that it is very important to remember where and who we came from. It is humbling to think of the harsh conditions that my great grandparents and grandparents endured, which made them take the arduous journey to escape and come to this country and live in near poverty. Following some of the rituals that they performed is a way of honoring and not forgetting them. For me, it feels good to be connected to them in this way.

CM: Where can people purchase your book, Rochelle? How can they connect with you or learn more about your work? What about Rex’s work? Is there still a way to discover and experience his poetry and paintings?

RC: My book can be purchased on Amazon.com by looking up the title and my name: Ode for the Time Being by Rochelle S. Cohen. I am, also, happy to send a signed copy if you email me at: rochellecohen19[at]yahoo.com

I would be very pleased to communicate with people about my science or poetry at the above email address.

After Rex passed away, I put together an anthology of his writing entitled: Skeleton Key. This book can be purchased on Amazon.com, as well, with Rex as the author. He is also the author of several books as follows, all of which can be purchased on Amazon.com.

Fiction: Desert Flower, Paper Moon

Fiction and Poetry: The Time Hotel, Night Without Stars, Constant is the Rain

Artwork, Poetry, Biographical Notes: X-Ray Eyes

Rex’s books and art and my book can, also, be seen online on the site:

Richard Seltzer’s Family and Friends (Scroll down to the bottom)

http://www.seltzerbooks.com/familyandfriends.html

CM: What has been the most rewarding aspect of publishing this collection so far? What do you hope people take away from your book?

RC: It is rewarding when people like yourself take it so seriously and appreciate the various sections. I hope that it helps people, who are grieving and that they know that they are not alone or “unusual” in their feelings, which is how I think grieving people feel sometimes.

I very much hope that people appreciate the ocean and its inhabitants, all of which are endangered nowadays. I hope it raises awareness in that respect. But, mainly, I hope that they see the beauty and elegance of these special animals. Also, I hope that they become aware of the great scientific discoveries, which are often hidden in the onslaught of other news. These discoveries give a feeling of transcendency and are important for our very being.

CM: In “Autumn’s Leaves Underfoot” you write about “our life’s game of hopscotch.” When you reflect on your own life, and all that you’ve created and accomplished and shared to this point, what has been most meaningful to you in terms of where your “pebble[s have] landed”? Any insights to offer on “hopp[ing] through the course”?

RC: Most meaningful is that I became the person I wanted to be. There were a lot of struggles at work and a lot of sacrifices in family life that I deeply regret. But, I am happy to stand with people, whom I admire, their way of being, people with whom I can identify. To have the respect of family, friends and colleagues is the most precious thing.

Hopping through the course was difficult. So many personal and professional obstacles in the way. My family, mother Edna, father Noah, sister Marion, and husband Rex were the very best in supporting, encouraging and stimulating me. My professors, colleagues and students, were always inspiring and supportive, as well. So, it’s always important to remember, appreciate and be very grateful to those who helped you “hop through the course.” One really never does it alone. It is always a group effort with those, who surround and love you.

CM: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

RC: Yes. Your questions are truly perceptive and made me think about things I know intuitively, but never articulated. And, some of your comments and questions made me think about things in a different way. Thank you for your insights.

CM: Oh, I’m glad. Thank you for your insights as well.

In “A Summer Place,” you speak about the souls “who see the beauty of nature as a poet.” You are definitely one of those souls and I feel enriched by having read Ode for the Time Being. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to experience love, loss, life, and laughter, through your eyes and heart.

RC: I thank you from the bottom of my heart for the rare opportunity to share these intimate feelings and thoughts with you and your audience. It is a privilege to have the occasion to express my opinions in this prestigious forum.

——

To purchase a copy of Ode for the Time Being by Dr. Rochelle Cohen, please click here. To learn more about the work of the late writer and artist Rex Sexton, please search for his books on Amazon.com.

For more interviews with authors, artists, and entrepreneurs, please join my mailing list.

——

Which scientific discoveries fill you with a sense of wonder and curiosity? What are some of your favorite marine animals? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

——

PLEASE NOTE: The opinions, representations, and statements made in response to questions asked as part of this interview are strictly those of the interviewee and not of Chloé McFeters or Tortoise and Finch Productions, LLC as a whole.

6 thoughts on “Dr. Rochelle S. Cohen”

I enjoyed reading this interview very much. I think it is interesting that Dr. Cohen and I had some very similar experiences in our background.

Science was never a strong point in my life. I found her descriptions of science very poetic and beautiful. She has seen a kind of beauty I have never met until now. I am grateful she has enlarged my thinking and seeing. I love that she is a dedicated scientist and a poet – a woman who has delved deeply into life and found many avenues to explore the connective tissue of it.

Thanks Chloe for introducing me to this woman. My word has been enlarged. Lynn H.

Dear Lynn,

Thank you for your most kind and thoughtful comments. I have been meaning to ask Chloe for your email address since told me that we had a lot in common.

I am deeply honored by your comments. I am very touched and moved. As a novice in poetry, I could not ask for a better response to my work. I was honored to be in the same newsletter as you.

I will respond more on your interview site, as I have been intending to do.

With warm wishes for a very happy, healthy and productive New Year.

Rochelle

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this informative interview with Dr. Rochelle Cohen. I had the pleasure of working with her, as well as being an attendant of her anatomy lectures. I’m glad to find out that she was recognized for her academic abilities by her appointment as the department Chairperson and in receiving the Distinguished Teaching Award. She is obviously a woman of many hidden talents as well. Who knew that she is also a poet? Congratulations on all of your many successes and for all of those to come! My deepest sympathy for the loss of your husband.

WOW! We were very good friends when Rochelle was at Rockefeller. I never knew she had this creative side. I remember meeting Rex when they visited NYC. I was sad to learn of his demise. Please tell Rochelle to contact me on facebook. Thank you.

OMG! I’m in awe of a Rochelle I never knew. An incredible writer and artist. So, so happy for her.

Her old friend, Anne-Marie

Dear Anne Marie,

I am going to write to right now. I am so thrilled to find you. I tried to find you years ago to no avail. I hope your address is the same. I do not have Facebook. My sister Marion tried to contact you on her Facebook page. With love,

Rochelle