A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of interviewing poet and writer Lynn Hoins. Lynn is the author of the forthcoming poetry book, Walking with the Tiger, and has been published in journals including Earth’s Daughters, Main Channel Voices, Wawayanda Review, Inkwell, Chronogram, and cine sera. She has two chapbooks published by Finishing Line Press: You Were Always Music and Called by Stones. She has taught many poetry workshops for The College of Poetry of The Northeast Poetry Center, Warwick, New York, as well as leading independent writing, journaling, and creativity workshops elsewhere. She frequently featured and read at open mics in New York State before she moved to Utah where she occasionally reads at open mics.

It was a pleasure speaking with Lynn about her writing, her inspirations, her mother’s poetry, and her love of Madeleine L’Engle and Julian of Norwich.

——

CM: I’m honored and excited to be learning a little bit more about you, Lynn. You’re a fascinating woman. What a pleasure this is for me! Thank you.

LH: The honor is all mine. Thank you for inviting me.

CM: I know you were born in Highland Park, Michigan, but Rome, New York was really home for you in the early part of your life. Tell us about Rome, about your childhood. What were some of your earliest loves and dreams?

LH: Rome is a small industrial city in central New York State located on the Barge Canal. It never felt like a city to me. We walked everywhere without fear. If you left your toys outside, no one stole them. Our street was quiet enough that we could safely ride our bikes and roller skate in it most of the time. In the summer we played kick-the-can and caught fireflies.

Rome is in the snow-belt. Snow fell frequently and stayed for months. In later years when bike flags had been invented, many drivers attached them to their radio antennas so you could see them over the snowbanks at the intersections. I loved to make snow angels and snow men, ice skate, and build snow forts.

I was crazy about school. Reading was my first love. My library card was my second. My friends and I played with our dolls, doll houses, and paper dolls by the hour. I still love miniatures. I started dance lessons early, tap and ballet.

Always a lover of books, I wanted to be a writer. That proved the strongest ongoing thread in my life. When I think of my childhood it seems quite idyllic, despite the war, compared with children’s lives today. It was simpler, more imaginative, and safer.

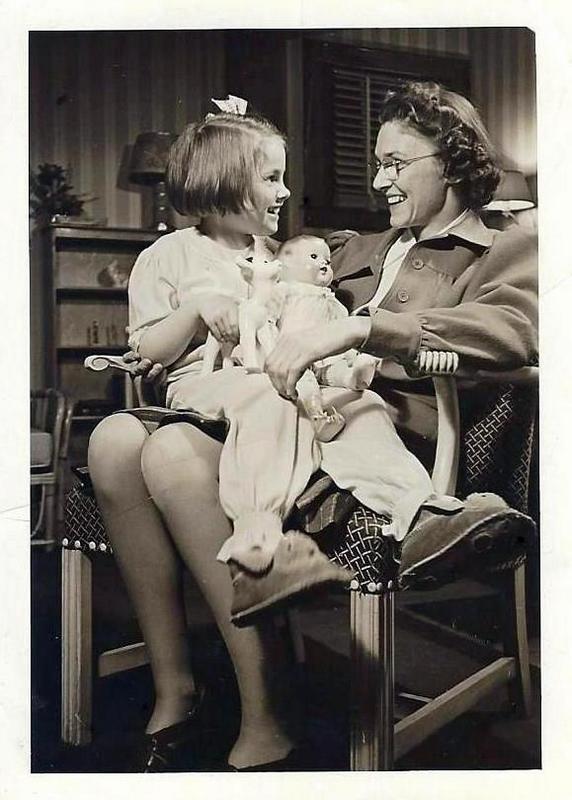

CM: Your mother loved books and read you many books when you were young. What are some of your memories of your mother reading to you?

LH: Being read to delighted me for as long as I can remember. Everyone read to me – my mother, my grandparents, my aunts and uncles, and my teachers. I don’t know if teachers do that anymore. In third grade Miss Barshied read us The Hollow Tree and The Deep Woods Book and The Hollow Tree Snowed-In Book by Albert Bigelow Paine. In sixth grade Mrs. Stedman read us I Married Adventure by Osa Johnson.

Mother loved to read poetry to me. I had memorized great swaths of it before I entered kindergarten. She read the Pooh books, Mary Poppins, At the Back of the North Wind by George MacDonald, The Wind in the Willows, nursery rhymes, fairy tales, A Child’s Garden of Verses, Beatrix Potter, Tasha Tudor, and Mr. Popper’s Penguins. I read her The Velveteen Rabbit. She always read to me before I went to bed as did my Grandfather when she wasn’t available.

I read to children I babysat for and anyone else who would listen. Reading aloud feels companionable. Sharing books that way encourages marvelous conversations. It also enhances one’s love of language.

CM: You developed a passion for the arts very early on in life. I just love that. Who and what first inspired that passion in you? What are some of your fondest memories of being exposed to music, dance, theater, art, etc. as a young girl and adolescent?

LH: My family were all lovers of the arts and blessed me with a wide, generous introduction to them including lessons in dance, music, and art. I never mastered anything, although I definitely enjoyed the exposure.

Although one may not be proficient in an area, one can still love the form. All artists need audiences. I have a Ph.D. in audience. I’m an appreciator. I love theater, film, dance, art, music in many different forms. No one had to drag me to museums or performances. I flew to them.

Mother and I listened to the opera every Saturday afternoon during the season. Even when I was very young, I loved it. Music has always spoken to me deeply, with or without words. Melody and harmony make my heart sing. Mother gave me tickets to the concert series in Rome and later to one in Utica, about fifteen miles east of Rome. During the forties the only way musicians and dancers could make money was by going on tour. I heard and saw all the top people.

Singing was my way to make music. I was in choirs from when I was eight until recently. Part singing, whether classical or popular, always made me happy. I loved the way the voices wove together. I sang my first requiem, the Fauré, with the Rome Civic Chorus when I was in my teens. It’s always been one of my favorites, partly because it was the first one I learned.

We always sang on road trips. Popular songs, camps songs, hymns, and folk music were all favorites because of the potential for harmony. I remember riding with my grandparents the day my aunt taught me how to harmonize. I don’t remember how she did it. I got it. Instantly. From then on, I could sing harmony any time I wanted to.

Between my freshman and sophomore year in high school, I worked backstage at a summer stock theater. I also tried out for every play and speaking contest available and usually ended up in them. Being on stage thrilled me. Maybe that’s why I enjoy teaching so much. Teachers are basically on stage every day all day long.

CM: You shared with me that your mother was a poet. What stands out to you about your mother’s poetry? What sorts of subjects interested her? Did she ever share her poetry with you? Looking back, what do you think your mother wanted to say with her writing?

LH: Mother’s poetry sang whether it rhymed or not. She loved playing with the French forms and sonnets. Most of her poems were quite spare. In few words she could encompass worlds.

Her biggest complaint was that her poems were out of style. Poetry changed enormously during the time she was writing. After being brought up on Shakespeare, Dickinson, and the romantic poets, her ear was tuned to a certain sound. The new “modern” poetry lacked musicality to her ear. I expect she didn’t care for confessional poetry either – too revealing of things better left unspoken.

Love and loss, nature, and allusions to the classics comprise the bulk of her work. Some poems are light, airy. Others feel heavy, depressive. Taken together they run the gamut of her life experience, including references to feeling outcast.

Mother shared her poetry with me as an adult. I don’t remember hearing any of her poems as a child although I always knew she was a poet. She wrote a wonderful poem about boys, which I like to think was inspired by her grandsons.

Boys

Dorcas Watters

I like boys.

They are more strange

than chrysanthemums,

more open than skies

that spill their blueness everywhere,

neat around the edges,

and self-contained

like a letter in an envelope.

What did Mother want to say? That’s a good question, Chloé. I’m not sure she was trying to say anything specific. Perhaps she was clinging to who she was, to not lose herself.

Stranger

Dorcas Watters

How to tell them that I grew

In loneliness and fear –

That she whom once they used to love

Will never again be here.

Oh let them use appraising eyes

To see me as I near

For more than she I used to be

Comes, when I come here.

And as, how long ago, they loved

The child to them most dear,

Perhaps they’ll love the woman grown

In loneliness and fear.

CM: When did you first feel drawn to write? How did your mother and other close family and friends feel about your writing ambition?

LH: I don’t remember not wanting to write. I was always in love with words and story. They gave meaning, instruction, authority to my life. Life was story. My imagination always worked overtime conjuring characters who demanded stories of their own.

Mother always supported my writing. She put a brass door knocker on my bedroom door. I closed the door when I was writing. She would come upstairs, knock on the door, to warn me it was time to stop writing and move on to some other activity. She always gave me at least ten minutes to wind up what I was working on.

Because I was so definite about being a writer the rest of the family and my friends believed me. I don’t ever remember anyone saying I couldn’t. My inner doubting voices said it. My friends and family didn’t.

CM: Did people’s reactions to your early writing shape how you approached your own creativity or identity as a writer? If so, in what ways?

LH: I once wrote a poem with the words Mother Nature in it. My mother told me Mother Nature was a cliché. I didn’t understand she was treating me seriously as a poet and trying to be helpful. I thought she meant the poem wasn’t any good. Given my need for perfection, I allowed that one comment to shut my poet-self down for years. I didn’t have enough sense to ask for elucidation, and she didn’t understand the weight of her words on me.

College was not a happy experience for me. I had sailed through public school doing well. My skills and inability to ask for help did not serve me on the college level. Although I occasionally wrote good papers, many of them turned out to be the worst writing of my life. I received enough negative feedback that I no longer believed in myself. By the time I graduated, becoming a writer no longer figured in my plans.

CM: You have always been a woman of strong faith and your journey along your spiritual path began when you were still quite young. How did those seeds of your faith first take hold in your mind and heart? How does your faith inform your art, if at all?

LH: My spiritual journey began in Sunday School when I was five. Our teacher was a woman of strong faith and delight in it. The delight was contagious. I was immediately hooked. Sunday mornings became the treat of the week. Learning Bible stories from her was delicious. Joy abounded in that room.

My grandmother was also a woman of strong faith. I spent a great deal of time with her when I was very young. For seven years I went to her house for lunch every school day. She and I remained close always. Her love and kind advice taught me much of what I know about being Christian. She stressed that God loved everything God made. Nothing was left out. No one was exiled, and no one was excused from exiling another. She practiced the golden rule every day of her life and left the world a better place for her presence in it.

Chloé, I don’t know if my faith informs my art. I hope it does. Once in a while a little piece of wisdom comes out of my pen. That might be faith in action. Perhaps some of my poems give a taste of faith. In Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art, Madeleine L’Engle used a term I love in speaking of an artist as a willing “birth-giver.” I hope in some small way I have been a birth-giver.

CM: Seeing John Brown’s Body, the epic poem by Stephen Vincent Benét, had a significant impact on you. How so?

LH: My mother took me to a reading of John Brown’s Body when I was a sophomore in high school. It toured the country before opening on Broadway in New York City. The production was directed by Charles Laughton and starred Dame Judith Anderson, Raymond Massey, and Tyrone Power. I had never read it and had no idea that the evening would change my relationship to my own language.

It’s the story of the Civil War told from multiple points of view in poetry. Stark and lilting, fierce and gentle, the words rolled over me engulfing me in a beauty I had never experienced before. As a child I rolled words around in my mouth for the sheer joy of it. That evening words came in wave after wave pulling my emotions in every direction. I understood the power of language. The writer in me was nourished and encouraged. It was a defining evening.

CM: After graduating from Antioch College, you decided to become a teacher, and enjoyed many interesting adventures in your teaching life. How did you come to the decision to teach? Please tell us about your time in the Netherlands and at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden.

LH: I didn’t decide to be a teacher. Teaching chose me. I was never properly qualified for any job I had. I accepted an invitation to teach in The Netherlands because I wanted to see Europe and my almost-fiancé was stationed in Germany. I thought I was to be an assistant teacher. I had no idea I would be the English half of the school. Had I known that, I never would have gone. Totally unqualified, I showed up on the doorstep of the small international boarding school and was led to my classroom – the English half of the school – and began teaching my students ages 5 to 13. I was never more than a quarter lesson ahead of any of them, and I had never had that much fun in my life.

Right after I graduated from college and married, we lived in Brooklyn. A relative of my husband worked at The Brooklyn Botanic Garden. When she heard they were looking for a teacher, she suggested me. Despite telling the head of the education department I had no knowledge of botany, her question was, “Can you teach?” I said yes. Once I got over my initial panic, I loved almost every moment of teaching there. The kids were delightful. Some of the New York City School teachers were not. The BBG offered an in-service course for teachers which some took thinking it would be a snap. They talked during class, snuck out to get coffee at the little luncheonette across the street, and screamed about having to take a final exam. I sometimes shuddered for the children who had to sit in their classes for a year.

Teaching in Brownsville, Brooklyn at an experimental public school was challenging. The students were poor, often lacked basic skills which put them behind before they even started school. Team teaching gave the children more one on one attention. In prekindergarten and kindergarten there were two aides as well as two teachers per room. Some of our first graders had never been to school before, didn’t know colors, numbers, letters of the alphabet. It was some of the most difficult and rewarding teaching I’d done at that point.

St. Vincent’s School, a private junior and senior high school for troubled young men, opened a lower school for children who could not be contained in public school at that time, either because of behavioral problems or learning challenges. Team teaching was necessary here to insure everyone’s safety. I cried every day on the way home on the bus the first few months. The students’ problems seemed insurmountable. In some cases they were. With others we had some success.

Getting permission to take the young ones out on field trips was one of my goals. It was crazy, but I took them to the Statue of Liberty, to the homecoming ticker tape parade for the released hostages, and to concerts. Didn’t lose anyone and was proud of how well they behaved when necessary. In the classroom they would act out often. On trips they clung to us and timidly enjoyed themselves.

I loved teaching writing and English and American literature to high school juniors and seniors in a small Catholic junior seminary. My poor college professors would have been horrified. They knew I wasn’t qualified. The headmaster disagreed. Even though I was often unorthodox, the classes did well.

In later years I taught poetry and creativity classes for adults. I believe they grew me both as a teacher and as a writer. I never asked anyone to do what I wasn’t willing to do myself. I worked right along with them. Teaching makes one look at material in a different way. As I found ways of explaining techniques, my own improved. Mostly I think it was the frustrated actress in me that loved teaching so much. I also loved watching students, children and adults, bloom.

CM: What are some of the things you most loved about working with young people? Did your students teach you anything in return? If so, what?

LH: I loved kids’ enthusiasm, curiosity, willingness to work. They stretched my boundaries by their questions, often unanswerable. The young ones were eager to learn, open to new ideas. The older ones pushed my tolerance and understanding. They often showed me grit. Many of the children I taught came from difficult family situations, needed to be fierce to survive. I had to find ways to teach them how to behave in a safe environment without eliminating their need for fierceness in their unsafe outside environment.

They taught me about courage, loyalty, and laughter. Many assumptions I had about life needed serious revision. They helped me recognize this. They taught me to be more humble, to be able to admit I didn’t know, and to cry with them when appropriate. They were real and demanded that I too be real.

CM: We both adore the poetry of Mary Oliver, who passed away in January of 2019. Do you remember first discovering her work? What are some of your favorite Mary Oliver poems? Why? What about her and her writing resonates strongly with you?

LH: My friend Claske Franck lent me one of her Mary Oliver books of poetry. It might have been Red Bird. I had been aware of Oliver prior to that but reading many of her poems together was a different experience than occasionally reading one or two. I fell in love.

Of my many favorites, I’ll just mention one: “A Postcard from Flamingo.” I love the idea of singing hands.

Her precision with language and the musicality of her work overcome me often. The spiritual layer in her poetry touches me deeply. Her connection to nature opens my eyes and heart to see my own surroundings with more attention, clarity, and delight.

CM: You credit the British novelists Elizabeth Goudge and Rumer Godden with teaching you to love stories. When and how did they do that?

LH: Both of these writers wrote adult and children’s books. I met them originally through their children’s books. Neither of them wrote simple stories. Godden often had terrible things happen even in her children’s books. Happy endings were never guaranteed. Goudge wrote a great deal about faith and trust in her books – how people abused it and/or were redeemed by it. These always drew me in. Both writers often chose unexpected characters to star in stories and both wrote children very well. Because Godden grew up in India, a number of her books were set in that area and included problems between the British and the people of India. Her plots often stressed difficult relationships.

Black Narcissus by Godden stressed the difficulties of English nuns in a foreign setting. It was made into an excellent film. A later book, In This House of Brede, set in England, also told the story of nuns. In this case the plot revolved around inner turmoil rather than outer. Some of my favorites of her adult novels have young protagonists: An Episode of Sparrows, The Greengage Summer, The Battle of the Villa Fiorita.

Green Dolphin Street may be the most well-known Goudge book. My favorite is The Scent of Water, a story within a story. There is a scene where one of the characters talks with a priest who understands about mental illness and addiction. He tells her there are three prayers, three words each. If she can hang onto those, she will always be all right. Those three little prayers — “Lord have mercy. Thee I adore. Into Thy hands.” — have saved me over and over. I pray them every day.

CM: Over the years, you attended many retreats and workshops led by Madeleine L’Engle, author of the Newbery Award-winning science fantasy novel, A Wrinkle In Time. Tell us about the influence that Ms. L’Engle and her writings had on your own life and art.

LH: Most people would cite her book A Wrinkle in Time as their first contact with Madeleine L’Engle. When I was a child, it did not yet exist. My son introduced me to it. My mother sent me three of her journals, A Circle of Quiet, The Summer of the Great Grandmother, and The Irrational Season. I was immediately hooked. I read everything I could get my hands on – adult and YA fiction, nonfiction and poetry. I became deeply immersed in her worlds. Here was a writer who spoke to my love of story and my soul.

Each year she gave a writer’s workshop and a silent retreat at Holy Cross, an Episcopal Benedictine Monastery in West Park, New York. The monastery is situated on the western bank of the Hudson River across from the Vanderbilt mansion in Hyde Park. The combined workshop and retreat lasted five days. Not everyone stayed for both. Before I had the courage to go, I drove into Manhattan to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine weekly one Lent for a series of talks she did with her spiritual advisor Cannon West. I was bowled over and determined I would go to a workshop to experience writing with her.

I became one of the regulars at those annual conferences and, when I could, stayed for the retreat as well. She encouraged, treated us as equals, and brought out the best in everyone. Her writing assignments stimulated excellent writing. She stressed that good writing was true, by which she did not mean factually accurate but mythically, soulfully true. She talked about serving the work, listening to the work, getting out of the way of the work. She never steered me wrong. It all made sense to me. I highly recommend Walking on Water, one of my favorite books.

CM: Two other major influences for you were the Dutch artist and writer Frederick Franck and his wife Claske Franck, and you spent many years with them at their sanctuary, Pacem in Terris, in Warwick, New York. Tell us about your relationship with the Francks and about the unique space they created in Warwick. What are some of the most meaningful things you took away from your times shared together?

LH: A friend said Pacem in Terris was a good place to hear classical music. I went. It was so much more. When the Francks bought their house in Warwick, New York, they discovered across the Wawayanda River a strange looking edifice, the stone foundation of a burned down mill filled with garbage. They bought that tiny piece of property squeezed between the river and the railroad tracks. Frederick, an artist and sculptor, began hauling out garbage. Eventually, Pacem became a transreligious sanctuary. Its acoustics were extraordinary. Frederick also placed his sculptures around the field behind their house and made another sculpture garden behind the little caretaker cottage down the road.

Pacem became one of my spiritual homes. I took my senior writing class there for a quiet day, was invited to help with spring cleanup, and then ushered at concerts. Eventually I became the “box office” for the concerts sitting on my little folding chair at a metal folding TV tray table. Often, I held an umbrella with one hand while I made change with the other.

Before that I helped Claske write thank you notes for donations and answered other mail. I did some manuscript typing and lots of filing. I drove Frederick to Newark, New Jersey when Claske was ill to give a talk before his sculptures were installed in a resurrected part of that desperate city. I worked on several of his books. I became one of the regulars in that ménage, even sometimes house sitting during the winter while they were in Europe. I accidentally tamed their cat Yata and turned her into a lap sitter.

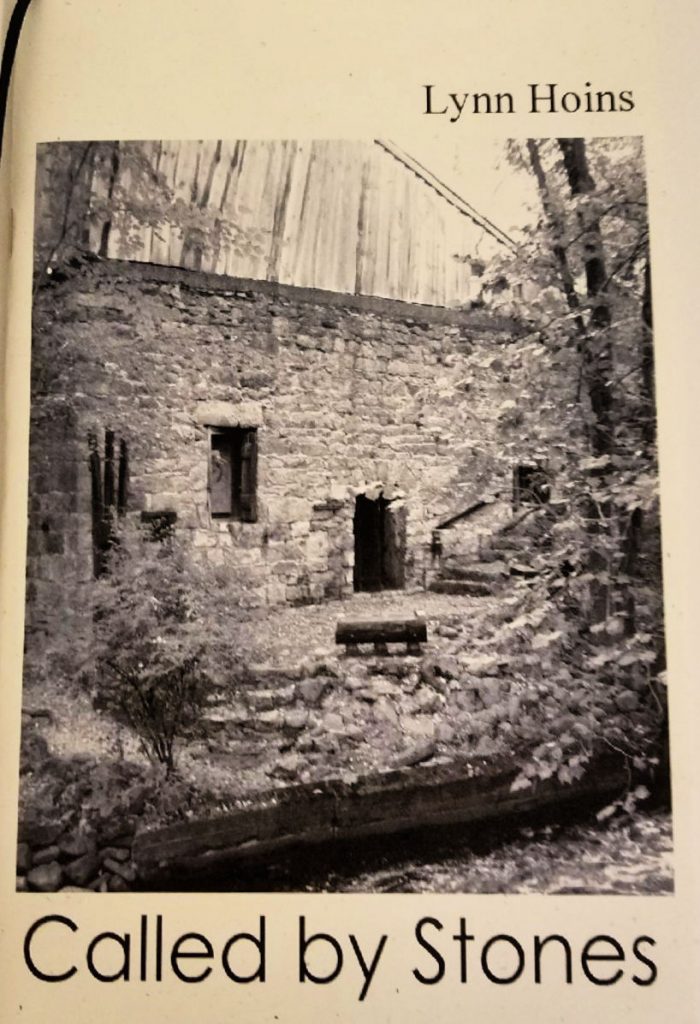

Pacem in Terris healed me at a time when my life was a total mess. The place itself healed me and the Francks, who with love and listening and allowing me into their world, also healed me. I began to write more poetry and fiction. Pacem birthed a book of poetry, Called by Stones.

CM: You and I also share a love of the visual arts and one of our favorite artists is Marc Chagall. As you know, Chagall worked in many different artistic formats. When it comes to his work, do you prefer one format over the others? What are some Chagall paintings you love and why?

LH: I love Chagall, because he often makes me laugh. There is much joy in many of his paintings. His use of strong color, his repeated motifs, give an iconography I relate to. He uses a great deal of blue and red both favorites of mine. All of his work appeals to me – paintings perhaps the most, because of their glorious colors.

I own three reproductions, two large and one small, and one numbered print from the Arabian Nights. One reproduction, “Feathers in Bloom,” and the print, “Mounting the Ebony Horse,” are very blue. The other two are predominantly red: “Birthday Surprise” and “The Bride and Groom of the Eiffel Tower.” They have traveled with me from place to place. They make my dwelling home.

CM: It seems we both came to truly appreciate Vincent van Gogh’s work a little bit later in life. What were your reasons for this, do you think, and what changed? I love the story about your van Gogh room. Would you be willing to share that story here?

LH: I needed to expand my understanding of beauty before I could take in his work. It was a little too wild for me when I was younger. I picked up tortured feelings from it, perhaps influenced by living with a person who was tortured at times. I think they scared me. I still feel the torture at times, also the wild exuberance of the painter. His use of color, his abandonment of traditional ways of seeing and portraying what he saw opened my eyes and heart.

I was house hunting and found a little yellow house I instantly loved from the outside. The owner was hesitant to show me the front bedroom. She assured me it could be repainted. I walked into it and fell in love again. The woodwork and wainscoting were deep Van Gogh blue, the upper half of the walls Van Gogh deep yellow. Around the top of the walls was a border of Van Gogh’s starry night. I knew I wouldn’t change a thing and the room would become my writing sanctuary. I spent many happy days and hours in that room. Overnight guests stayed in my bedroom. I slept in there on the floor on a blowup mattress. I only shared it with my cats.

CM: How important do you think it is for a writer to have a “room of one’s own,” whether that “room” is a physical space, or perhaps a place one is only able to visit in one’s mind? How important to have a space where we can feel free to be who we are and to create what we long to create, even if only initially in our imaginations?

LH: I think it’s very important. Creative people need space to formulate as well as produce their work. No matter what one’s “art” is, to take it seriously enough to create space for it in your heart as well as in the world, will give the work and the artist a better chance to flourish. No matter where I’ve lived, I’ve always carved out a spot to be quiet. Even in college where there was frequently no peace in the dorms, I found a carrel in the stacks at the library where I could work and safely leave my books all semester long. That became my sacred space. No one bothered me there. Sometimes it’s a special corner and chair; once I outfitted a closet with a board on top of two filing cabinets. I believe freedom to create can be greatly enhanced by choosing special places to be still to receive inspiration. However or wherever isn’t important. Giving one’s Self that gift is.

CM: Over the years, you’ve taught many classes on journaling and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. One of the primary practices in The Artist’s Way is something called Morning Pages. Can you tell us about this creative discipline and how you have used these pages or other journaling practices throughout your life? What, if anything, has been the reward of doing so? What would you say to those who might be considering a journaling practice or who have tried but haven’t quite been able to make it stick?

Morning pages are three 8 ½ x 11 pages of long hand free writing done first thing every morning. I’ve been doing morning pages consistently since 1988 or 1989. Before I did those I was writing what I called Mourning Pages because of the losses I needed to deal with at that time. I also studied Progoff Journaling which also stresses writing by hand. This is a much more complicated system and very life enhancing. I was unable to sustain it on my own.

Morning pages are simple. One just spews everything out on the page in no particular order or form. Whatever pops into one’s head, down it goes. In this way one can record important events and feelings as well as petty little garbage. It’s a way of clearing out and looking at things without dumping them on anyone else. One starts the day fresh.

These pages are so much more than garbage pails. They also can be used to work out ideas especially about one’s creative projects. My morning pages are filled with ideas, trial and error, pieces of story, poems, inspiration from what I’m reading, have listened to, or watched, snatches of overheard dialogue that might come in useful, spiritual guidance, and to do lists. Lately I’ve ended each day with a line called “Intentions.” I’ve discovered choosing to do something with intention is very powerful.

For anyone considering giving them a try, I make these suggestions: number your pages, mark in the margin any important things you might need to find again, turn to the back of the book and make an index with the page number and a brief title – poem, ideas, to do, insight – to facilitate finding the nuggets. Julia Cameron suggests not to reread your pages for at least several weeks. If you like color, use different colors for different days. The earlier you write after you wake up, the closer you will be to your dreams and yourself without its masks.

CM: What did you learn about writing and creativity through teaching those classes?

LH: Because I never ask others to do what I am unwilling to do myself, I always do what I assign. This has not only taught me new things about myself and how I create but also increased my body of work. I find working with other creatives very stimulating. They open me up to new ideas, broaden my understanding, and encourage me to do my own work. I often use prompts when I teach. Prompts take me places I never would have thought to go.

CM: You consider yourself a “story spinner.” What does that mean for you? What kinds of stories do you like to spin? Where do you find your inspiration? Do you have any writer’s rituals to help you with your spinning?

LH: Stories come to me, often beginning with characters. They show up in my morning pages, they whisper in my ear on walks, they shout out in the dentist’s chair. I take these little snippets and spin them into stories. I mostly write fiction. If an idea is too slight for a story, it will often become a poem. Occasionally I’m inspired by odd things I see or hear; sometimes incidents from my past can be woven in but changed to fit the story.

I also call myself a scribe. I often feel as if a story isn’t coming from me but through me from elsewhere, not something explainable to the rational mind. As for rituals, long pieces sometimes end up with a soundtrack and often with an image that keeps them alive for me.

When I was writing my memoir, I found a little green plastic soldier. He reminded me of my dad and sat on my desk as I wrote. It wasn’t until recently, I looked at him more carefully to discover he had a name and date on him. When I looked him up, he was a doctor in World War II like my dad.

If a tangle occurs, I may ask for help with it before I go to sleep. Eventually I wake up knowing how to untangle that part. Most of the time, the best thing to do is put butt in chair, warm up the computer, and begin where I left off. If stuck, it can help to retype the last paragraph or so. By the time I do that my fingers usually keep on spinning story.

CM: Your fiction and poetry have been published in a number of publications, including Inkwell, Oxalis, Earth’s Daughters, and Chronogram, and your writing has won awards from ByLine Magazine, The Poetry Society of Virginia, and others. What has all of that meant to you? What value, if any, do you place on publication? On prizes and awards?

LH: I love being published, winning prizes. It’s validating. Does it make me a writer? No. Writing makes me a writer. To submit takes more than courage. It takes the ability to continue writing despite rejection. Inevitably, there will be many more rejections than acceptances. If you take them personally, it may undermine your confidence in yourself and lead to abandoning your writer self. That’s dangerous. Marianne Moore said she never gave up on a poem until it had been rejected 32 times. Madeleine L’Engle said she had enough rejection slips to wallpaper her whole house. If you want to be published, rejection slips will be the norm. Be prepared.

Contests are like buying a lottery ticket. You have to be in it to win it. However, your chances of winning are low. Many contests have thousands of entries. Ten to twelve or fewer are sent on to the final judge. Getting past the gatekeepers is difficult. Contests also cost money. If you receive a copy of the issue with the winners in it, it may be worth the investment. Check the contest out online. If you can read winning entries do so. That will give you an idea of the quality of writing that won with that particular judge. It may be better for your portfolio to have credits of publishing in journals than contests. Many agents and publishing houses read journals looking for new talent. Don’t underestimate any publishing credit if you have a strong desire to pursue publication.

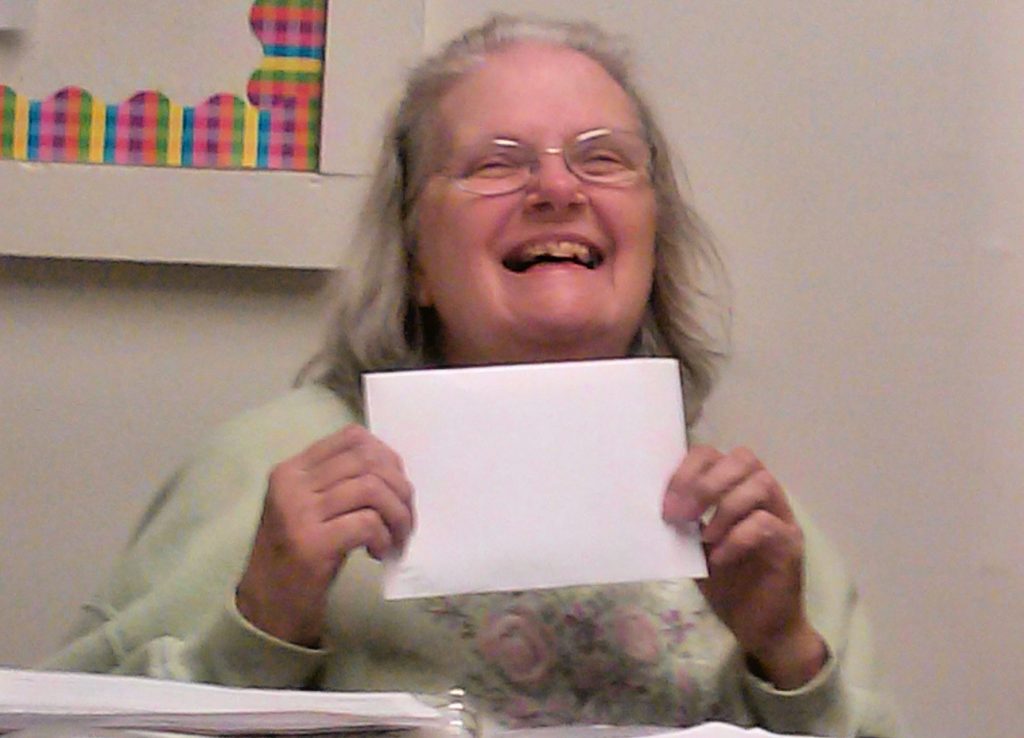

CM: You are the author of two chapbooks of poetry, both published by Finishing Line Press. Please tell us about Called by Stones, which you mentioned earlier, and also You Were Always Music.

LH: The poems in Called by Stones are inspired by Pacem in Terris and the Francks. It is my outpouring of love and thanksgiving for the place itself and the people who created it. They enriched my life and gave me a haven when needed.

You Were Always Music contains poems celebrating love and coping with loss. Love and loss go hand in hand throughout everyone’s life. Loss can be devasting. I hope by being open about my own losses, others might find comfort and understanding about theirs. My feelings are not unique. I felt isolated in them which made them more difficult to endure. Perhaps sharing them will help others feel less alone.

CM: I was deeply moved by You Were Always Music and how you were able to capture many of the subtleties and nuances of mourning and loss. There is such agony and such love in those poems. How does it feel to go back and read some of those pieces today?

LH: Chloe, that is an excellent question. I love both of my poetry books. This was the first one. The second is easier to read aloud at poetry venues. It’s a celebration book. You Were Always Music both celebrates love and holds the pain of endings. It’s easier to read the celebratory ones than the ones with the rawness I sometimes still feel when reading them. I love them. I rarely read them in public. When I was writing them, I had no idea of their power. Now I am a little awed by my own work. It’s as if they were written by someone else.

CM: Do you find that people sometimes assume that your work is more autobiographical than it actually is? What do you believe is the importance of “truth” in writing?

LH: The only thing I have written that is truly autobiographical is my memoir, Letters to My Father, currently looking for a home. My basic writing is fiction. I am a good enough writer that my fiction often sounds and feels real. Perhaps that is because the feelings are always real.

My poetry bounces back and forth. The feelings are always real although the surrounding framework may be a composite or total fiction. There are a series of cemetery poems in You Were Always Music that many people think are autobiographical. They are not. I never know if I should admit that or not. Does it make them fake, invalid? Pieces of them are real. I agree with Madeleine L’Engle that truth, if you mean sticking only to the facts, is often not the whole truth. She questions, “Is it true?” By that she meant true in spirit. I hope my writing while often not factual is true in spirit.

CM: Your father was killed in World War II and you were named after his identical twin brother, your Uncle Lynn, who also served in the war. What would you like to share about your epistolary memoir, Letters to My Father? How do you believe that writing can help to free us, to heal us, to lift some of the burdens of both the past and present?

LH: The most important thing to celebrate is it is complete. After working on it for thirty years, during which time it often gathered dust on the shelf, it is now actively looking for a home. I had to grow into the woman who could write the book with compassion.

I didn’t know my parents were divorced. My father was killed in World War II when I was eight. Some years later I discovered he had written letters to me I never received and were never answered. I felt terrible about that and guilty, although the guilt was not mine. I couldn’t answer what I never got.

The memoir contains my father’s heartfelt letters to me, letters written in my young child’s voice to him, and letters written from his adult daughter. In writing this book two things happened. I felt I righted the wrong done to my father, and I became freed from years of unearned guilt.

I believe writing our life story gives us a chance to understand in a different way the story we have been telling for so long. We often need to reframe our young stories given our adult understanding. I was able to express my feelings, accept them, and let them go. I feel so much lighter now. When we write our stories out, we understand how they affect us and how we continue to have difficulties in similar areas, because we are not yet healed from the original happening. The tale/tail is still wagging the dog. Perhaps the biggest gift is accepting ourselves as human beings. Many of us have survived difficult challenges to become the people we are today. The question is, “Is anything holding us back from being the best person we can be and having the best possible life today?” If the answer is yes, we need to look to the past to see what can be healed.

CM: It took you many years to fully claim your identity as a writer. When and how did that finally begin to shift for you? What did it feel like once it did? What would you say to those who haven’t yet been able to fully claim their own identities as writers, artists, and creative souls?

LH: Once I left college, I let go of the idea of writer as my profession, even my identity. I married, taught, raised a family, taught some more, and moved out of the city – at least 24 years of not writing. The itch was still there. I didn’t scratch it, until I started teaching at the high school level. Day after day I prepared lessons about poetry, fiction, plays, essays. I watched PBS and was inspired by many programs. Story became important again. I began nibbling at the edge of writing. Suddenly the flood gates opened, and the words flew out of my fingers onto paper and into the typewriter. My cousin egged me into buying a small word processor. I was a closet writer. It wasn’t until I braved going to Holy Cross to Madeleine L’Engle’s workshop that I admitted, “My name is Lynn Hoins. I’m a writer.” I was terrified when I said it. Nothing struck me dead. From that moment on I never again denied my soul work. I was finally back home in my own skin. I knew who and what I was.

I hope everyone reading this will believe you are creative. I know you are. We were all born creative. Many were not encouraged in their natural creativity. Whether you are a creative teacher, engineer, gardener, crafts person, parent, homemaker, checkout clerk, you are creative. If you have always wanted to build something, tinker with something, make art or music, dance, act, write, you are also creative. Whatever makes you happy is probably part of your creative genius.

Think about a name for your own special kind of creativity. Now claim it! I AM A _____. Fill in the blank. Write it on post-its and put them up where you will see them, especially on the bathroom mirror. If you live with others and haven’t come out of the “hiding my creativity closet,” then hide the posts for now. Still write them. Say them out loud at least three times each, three times a day until the news gets into your brain and your heart. Once you acknowledge your creativity, it will expand and grow and be a gift, first to you and then to others.

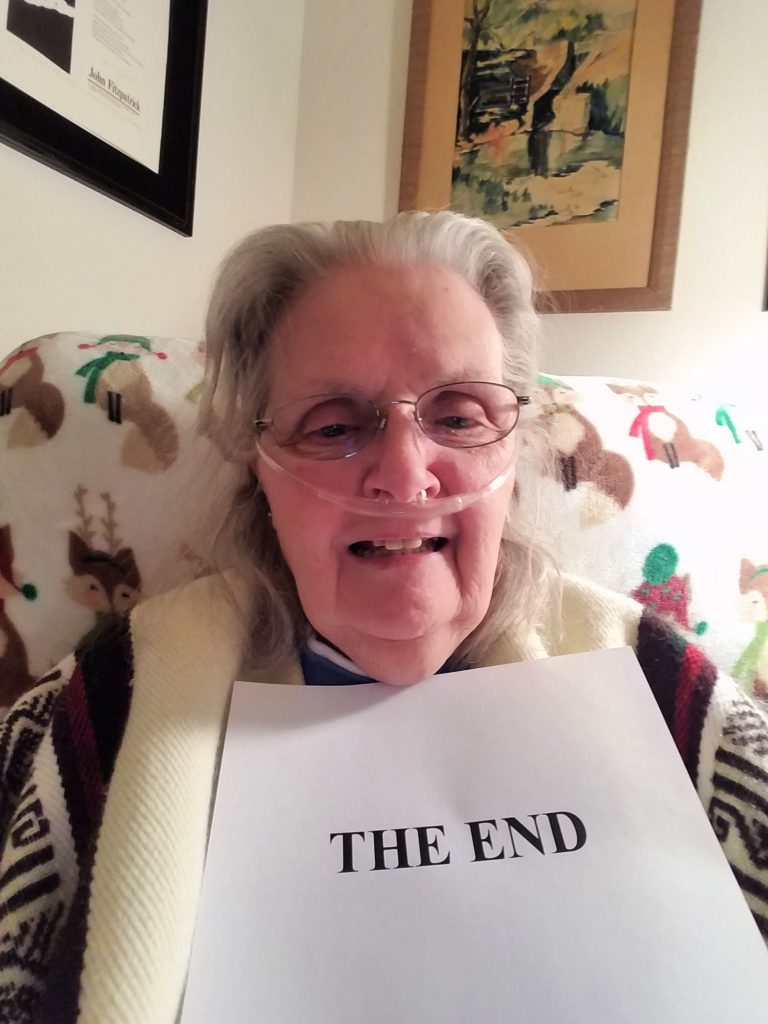

CM: You are living with pulmonary fibrosis (PF), a chronic and progressive lung disease for which there is currently no cure. What are some of the adjustments you have had to make due to your diagnosis and what has that been like for you? What would you like for people to know and understand about PF and living with a life-limiting illness?

LH: Thank you, Chloé, for saying currently no cure. You instantly made me feel less under the gun. The biggest change for me has been having to turn into a tortoise when I have always been a hare. I still want to stride out into the world. Creeping is not my normal gait. The oxygen I hardly notice, although I still jump up wanting to do something near by and get to the end of my oxygen tether with a degree of frustration and a laugh. Giving up driving and going out shopping on my own were difficult. Not being able to sing sometimes brings me to tears. I don’t do change well, so every change has been a challenge.

However, I am grateful every morning when I wake up and realize I have been given another day. I’m blessed that the things I love most – reading, writing, music, and film – are sedentary pursuits which I can still enjoy. My friends keep in touch by phone, email, texts, and Facebook. My family has taken very good care of me and fit my two most important pursuits, church and my writing group, into their calendars.

The hardest thing about PF is how exhausted I get doing little. I am surprised sometimes how tired I feel. I just received a tee shirt from an understanding friend that says, “Sometimes it takes me all day to get nothing done.” That about sums it up.

If you are working with, loving, someone with a life-limiting illness, I believe it is helpful to ask them what they need, what works for them. It’s important to understand the limitations they struggle with and to try to be patient with the symptoms. If these drive you crazy, realize how much more frantic they drive the person experiencing them. Acceptance, patience, and lots of laughter always help.

When people are at the end stage, it can be difficult for those witnessing the last days and hours. I urge you to remember the good times and seek help with grief. I want to be remembered for the good times, the laughter, and the love. I think most of us do.

CM: You have such a wide and interesting range of passions and interests. How have you continued to explore and enjoy the passions and interests that mean the most to you now, even if you aren’t always able to do that in person or in the same ways as before? You mention Facebook. How has social media been supportive, if at all?

LH: I desperately miss live performances. Even the best live coverage on TV doesn’t fill that lust. It’s not the same. My son took me to the opera last year. I was so thrilled and engaged that my breathing slowed down so much my oxygen kept dinging a warning that I wasn’t breathing. It was both funny and annoying, especially for the people around me. I was so exhausted afterward I was in bed for several days.

I’m grateful for the wonderful things people post on Facebook. There was one recently of an older gentleman playing a piano in an Irish railroad station and a stranger came up and joined him in an impromptu duet. It was fabulous. Then they both went off to their trains. It almost felt as if I were there. I was delighted that the Irish have pianos in RR stations for the public to play.

As much as I enjoy some posts like that one and the wonderful people I have met through Facebook whom I never would have met otherwise, I have to be careful because Facebook can be a huge time eater for me.

I have a friend who calls this “The Device Age.” I worry people are losing the ability to connect live with each other. Cell phones and the Internet can be addictive. However, I am grateful for staying in touch with those I love by phone, email, text, and Facebook. I feel less cut off from the world I can no longer participate in.

CM: I know that you are working on several pieces of writing at the moment, including a new poetry chapbook called Cries From the Heart. You also met your word count goal for a novel you are working on during last year’s NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month). What can you tell us about these and your other projects?

LH: Once I finally claimed writing as my way to be in the world, I dove into writing full speed ahead. Now that my time is spooling down, I am working to complete the many unfinished projects gathering dust on the shelf. Some are novels that didn’t quite make the grade and one is a nonfiction book. Sometimes writing gets abandoned, because I have to grow into it. Cries from the Heart is one of those projects. It is a book of prayer poems I wrote over a long period about mental illness looking in from the outside. It is painful to watch someone you love in pain whether physical, mental, or emotional. Not much attention has been directed to that kind of pain. This is a heavy book. Whether it will find a home or not, I am uncertain. My hope for it is that it will resonate with people who have felt what I felt and give some comfort in seeing they are not alone.

NaNoWriMo happens every November when writers are challenged to write a novel of 50,000 words in 30 days. If nothing else, it gives a writer a chance to practice craft and set up a regular writing practice. It’s definitely doable if one thinks in 1,167 word daily bites. My next project is to resurrect one of those NaNo novels, Some Enchanted Weekend, a love story between two older divorced people who meet when she crashes his son’s wedding reception.

This past 2019 NaNoWriMo I did begin a new novel, a chapter book about Alexander, age eight, who kept popping up in my poetry in April 2019. Unfortunately, we only have 15,000 words so far, because I moved to a new apartment unexpectedly in the middle of November. As soon as all the boxes are unpacked, I will be back on the page with Alexander, Elizabeth, and their American Indian friend. Spoiler Alert: Time travel and ice cream are involved.

I’d love to write a weekly column of snippets about life. I want to publish the chapbooks ready to go and put together a full poetry book. I came into being a poet much later than being a story spinner. Poems satisfy me because I can finish them. They are not easier to write because there is a huge challenge in making every word count, but they are much less cumbersome than a novel.

CM: Madeleine L’Engle once said, “…to grow up is to accept vulnerability…To be alive is to be vulnerable.” What has your life to this point taught you about accepting vulnerability?

LH: How hard it is to be truly vulnerable. This quote comes from her book, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art. After surviving the vulnerability of childhood, possibly the first time I understood vulnerability in the human sense was when I fell in love. Love is our mission and our opening ourselves to both joy and pain. Becoming a parent increases that awful and awe-filled place in our hearts where we give everything we have to give and know the possibility of loss. Love requires accepting vulnerability.

As children we were taught to be independent, self-sufficient, and self-protective. To me, being vulnerable means to allow others in and to show how human and fallible I am. It sometimes feels like the exact opposite of my early training. As I have aged and developed a life-limiting illness, I feel vulnerable in a new way. I can no longer depend on my body to do what it used to be able to do. Learning to ask for help is humbling and necessary. I confess, I don’t like it.

CM: Another thing we share is our love of a passage written by Julian of Norwich, a mystic, theologian, and English anchorite of the Middle Ages. The passage is taken from her Revelations of Divine Love: “…all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” I know that you have your own spin on this quote and I’d love for you to share what that is and what that passage means for you. How does your interpretation of its message help to sustain you today?

LH: This is my constant prayer. It keeps me standing when I want to fall down. It gets me through the places where nothing feels solid under my feet. It sustains me. It puts my trust where it needs to be. Madeleine L’Engle taught me to add these three words to this prayer: NO MATTER WHAT. It always works for me. Every time.

CM: What feels truly supportive and nourishing for you these days? What brings you the most joy?

LH: Saying Julian of Norwich’s prayer and the three three-word prayers I mentioned earlier supports me. My faith, faith community, hospice team, family and dear friends support me. Telephone calls from those I love give me great joy. I am nourished by the books I read, music I listen to, my writing group, Hershey’s Gold candy bars, and ice cream. My doctors have been of infinite value getting me through this health challenge. It gave me immense joy to finally complete my memoir. Writing is still possible and fills my heart with joy. My beautiful brain still functioning is a miracle I celebrate daily. My son and daughter support me physically and emotionally. Which ever one I am with, they treat me like a precious jewel. My heart overflows. I feel blessed each morning I am given to greet a new day and love and be loved. Life is good.

CM: What gifts have your favorite writers given to you over the years? What gifts do you hope your writing gives to your readers?

LH: Writers have taught me how to live and love. They have peopled my world with fascinating characters to enjoy, treasure, and learn from. My horizons have expanded. Hopefully my understanding has as well. Books have filled my life with variety, laughter, tears, and joy.

I hope my writing touches people’s hearts and comforts them. Perhaps my words will give them their own words to express both their pain and their joy. I hope they will love my character as much as I do and sometimes laugh. I can’t be funny on purpose, but some of my writing does make people laugh. That makes me happy. It would be wonderful if my writing caused readers to ask questions and opened cracks for light to come into dark places. If people enjoy reading my work as much as I enjoy writing it, that would be splendid.

CM: Where can people learn more about your writing and where can they purchase your chapbooks?

LH: In early 2020, I’ll be launching my new website, www.lynnhoins.com. In the meantime, anyone who is interested in being notified when the website goes live can visit now and sign up to receive an e-mail when that happens. Called by Stones is available from me or Finishing Line Press.

CM: One of your poems is called “love ain’t like that.” For me, that poem is about how love often exists in the tiniest and least “romantic” of gestures, in the sacrifices we sometimes make for those we love. Sometimes those actions and sacrifices seem to go unnoticed or unappreciated, but in the last line of your poem, the narrator reassures the listener that is not the case: “Don’t think I don’t notice.” What inspired that piece? How important is noticing and appreciating in relationships? In life? What have you noticed well? What do you love noticing and appreciating lately?

LH: I enjoy writing poems in voices other than my own. This poem was actually written for a class I was taking at a local community college. The assignment was to write a love poem for Valentine’s Day that wasn’t cliché or what one would expect. This was the poem that came out of my pen, published in Chronogram, March 2014

love ain’t like that

Lynn Hoins

I went to the store

to get you a card

but love ain’t like that.

Them hearts and flowers

is all very well

for the rich folk up on the hill.

Here we do it different.

It’s more like my jeans

smellin’ fresh in the drawer

from hangin’ on the line,

or the extra half

a peanut butter sandwich

you put in my lunch sack.

It’s you hummin’ by the kitchen sink—

your hands rough and red—

too many dishes,

too much scrubbin’ floors.

Don’t think

I don’t notice.

I think noticing is the most important gift we can give one another. Noticing and listening. It’s easy to be lost in one’s own life and thoughts. I have a constant committee meeting going on in the squirrel cage of my mind over major decisions like where to live and minor inconsequential things like which brand and flavor of oatmeal should I buy. I can miss life and love whirling around in that cage.

I notice nature, especially birds and plants. Moving to Utah has given me a whole new landscape to learn. I notice children and pets. People in their infinite variety fascinate me. Their expressions, body language tell stories. I notice acts of kindness and acts of cruelty. The former delight me. The latter make me sick. I am rarely brave enough to interfere. I read moods and needs, something I learned as a child. This skill helped me become an attentive teacher.

Lately I notice the change in the light, many acts of kind help given me by strangers, how well my grown children express love, changes in weather, how delicious naps are, how many things strike me funny, how long and well I have been sustained by music, reading, and all the arts. I notice love.

CM: We started our conversation today by talking about how your mother used to read you stories when you were a young girl. When you learned to read, you then read stories to her in return, and as you shared earlier, one of the stories you read was The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams Bianco, which is one of my favorite books. I love the line about becoming real and how once one becomes real, one can never become unreal again. What has “becoming Real” meant to you in your own life? What do you hope for all those out there who are on their own journeys to “becoming Real”?

LH: Sometimes I didn’t know who the “real me” was. The roles I filled seemed overwhelming. I wanted to be real in those roles, to love well, to respond authentically. I hope I grew real with those I loved.

One of the gifts of aging is one seems to become more and more who one really is – good and bad. We lose some of our camouflage, show our true colors. My prayer is I become more loving, less critical.

For all of us I hope kindness and peace prevail. It isn’t easy to accept and understand much of what is happening in the world today. I believe that if each of us does the best we can to be authentic in our relationships using love and kindness as our guide, we can each effect the world in a more positive way. It is not easy to turn the other cheek, to allow differences in a loving way. Our survival depends on getting along. If in “becoming Real” we learn first to love and respect ourselves, it may be easier to extend that love and respect outwards. Real people are comfortable in their own skin. They can meet others with kindness because they don’t have to prove anything. The other part of becoming Real is inviting others to join us, to rejoice in connection and integration.

CM: Is there anything else you’d like to share?

LH: It has been a pleasure to answer these questions, Chloé. They have made me think and helped me grow. My hope for all of us is that “all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well…NO MATTER WHAT.”

——

Lynn and I are currently working on a book called Journey Into Poetry, which is scheduled for release in 2020. To be notified when the book is available for purchase, please join my mailing list.

To learn more about Lynn and her work, please visit her new website at

www.lynnhoins.com.

For more interviews with authors, artists, and entrepreneurs, please join my mailing list.

——

Who and what have been some of the creative influences and inspirations in your own life? What are some of your favorite poems and why?

——

PLEASE NOTE: The opinions, representations, and statements made in response to questions asked as part of this interview are strictly those of the interviewee and not of Chloé McFeters or Tortoise and Finch Productions, LLC as a whole.

4 thoughts on “Lynn Hoins”

Thank you Chloe for including me with these talented and compassionate women. I think you are an amazing interviewer. Your questions made me dig deeply to come up with answers. I see myself differently than I did. It was a privilege to be featured with them in your December newsletter. Thank you. Lynn H.

P.S. I can’t find one of these reply boxes for the whole newsletter. I loved your meditation at the beginning. It is beautiful, well-written, and sets the tone for this whole issue. I love the beautiful mandala you shared with us. I like the way you highlight parts of the conversations and scattered photos throughout the interviews. It broke them up nicely. This is a stellar newsletter. It makes me proud to be a part of it. Thank you. Lynn H.

Dear Lynn,

I greatly appreciate the opportunity to know you through Chloe’s insightful interview. I felt a sense of awe as I read your responses.

I loved reading about your childhood. The story about the library card brought back a good memory for me. Even as a very young child, I felt grown up to have one. Thank you for that remembrance. The entire story about reading was very moving and warmed my heart. The experiences with your mother were so beautiful . You certainly carried on her legacy in such a creative manner.

As Chloe pointed out to me, we have a lot in common. Growing up in Brooklyn, I often went to the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens. My father grew up in Brownsville. I loved that you went to The Netherlands, my favorite place on earth. I just looked up the works of Frederick Franck. Your description of Pacem in Terris is totally inspiring. I love the Chagall paintings that you describe so eloquently. And, I have a book of the Arabian Nights! A colleague gave it to me and I cherish it.

The descriptions of your family are very poignant. I loved reading about them and seeing their pictures.

It is hard to know where to stop writing about your interview. I was mesmerized the first time I read it and when I read it over several times. You are an extraordinary woman in all respects and an inspiration to me. Thank you for sharing your thoughts with me and others. Their brilliance shines throughout.

Rochelle

Dear Rochelle,

I’m overwhelmed by your lovely response to my interview. Thank you very much.

I’m glad some of my stories and memories prompted your happy memories as well. That is always a joy for me.

I love the things we have in common and would love to deepen the acquaintance begun through Chloe. Even though I am hopeless at science, I am interested in what you have discovered and worked with. I found your descriptions fascinating.

I love that we both came to writing poetry later. It is a special form of communicating. For me it is satisfying to have a short form to work with. My short stories always want to be novels. Poems remain poems. I appreciate that about them. And when I have something to say that hasn’t the weight to support a whole story, it will often make its way into a poem. I also find them helpful for portraying feelings, especially the difficult ones.

I read your interview a number a times also. I was totally involved in your life and processes. Looking forward to getting to know you better. Thank you again, for your kind and supportive response to my interview.

Warmest regards, Lynn